I will always remember the first spring I spent in China. While travelling around the countryside, the surrounding hills echoed with the pop of firecrackers and laughing children. To my surprise, the locals were not celebrating a wedding … They were paying respects to their dead.

Qingming Jie 清明节 literally means “pure and bright”, and marks the start of spring. In China and around the globe, the paths leading to graveyards are swept clear of brambles and nettles. Incense and paper money is burned. Offerings of tropical fruits, roast pig, cigarettes and wine are ceremonially served to ancestors. Finally, tombs are swept clean of dust and weeds, to show that ancestors are cared for.

As a family historian, I have a deep appreciation for Ching Ming’s quiet rituals. They create a space for us to contemplate our past and our place in the universe.

But a closer look at its history reveals that the purpose of Ching Ming was not always so black and white…

In this article, you’ll learn about the recurring politicization of Tomb Sweeping day throughout the years, and why this festival is so important to Chinese communities around the world.

A Short History of Ching Ming

For thousands of years, it was common practice for Chinese nobles, emperors, and peasants alike to commemorate the departed by sweeping their graves.

However it was only in the year 732 AD that Tang Dynasty Emperor Xuanzong formally declared Ching Ming “ancestral worshipping day”. The reason for this was not that people needed encouraging; it was exactly the opposite. Many Chinese had begun offering ancestral sacrifices as often as every two weeks, spending so much money on the ceremonies that it had started adversely impacting China’s economy.

In 1949, the victorious Chinese Communist Party banned Ching Ming due to its feudal connotations. Still, people continued to honor their ancestors, in quieter ways than before.

Then in 1976, Tomb Sweeping became the scene of the First Tiananmen Incident. When Premier Zhou Enlai succumbed to cancer, Chairman Mao and his clique were conspicuously silent, offering no public condolences. This did not stop the nationwide outpour of grief for Zhou, who was seen as an unflinchingly loyal figure in the Party. On the eve of Ching Ming, thousands came to Tiananmen to lay wreaths, flowers and banners in his memory. When the government cleared the square of offerings overnight, mourners returned en masse to protest against the central authorities’ disrespect of Zhou. The government finally swept in to quash the protest.

Over in Taiwan, Ching Ming was used by the Nationalist government to validate the KMT’s authority. After Chiang Kai-shek passed away, the government went so far as to change the original date of Ching Ming to April 5th – to commemorate their “glorious leader” Chiang’s death.

A “Sweet” Occasion

With mainland China’s opening up in the 1980s, the rituals were slowly revived, but Ching Ming was only reinstated as a public holiday in 2008. Since then, it has seen a resurgence in mainland China: in 2012, an estimated 520 million people visited cemeteries for tomb-sweeping.

Whereas cemetery visits are considered solemn occasions in Western Countries, Jingwen from Guangzhou, describes Ching Ming as a “sweet occasion”.

“To honor our ancestors, we usually buy a large piece of roasted pork, a whole chicken with its head and feet, 6 apples, steamed buns with vegetarian stuffing, and sugar cane as offerings. We stay until all the incense has completely burned out, and while we wait, we nibble on some of the offerings to ensure we are blessed by our ancestors in return.”

Jingwen Liu, researcher at My China Roots

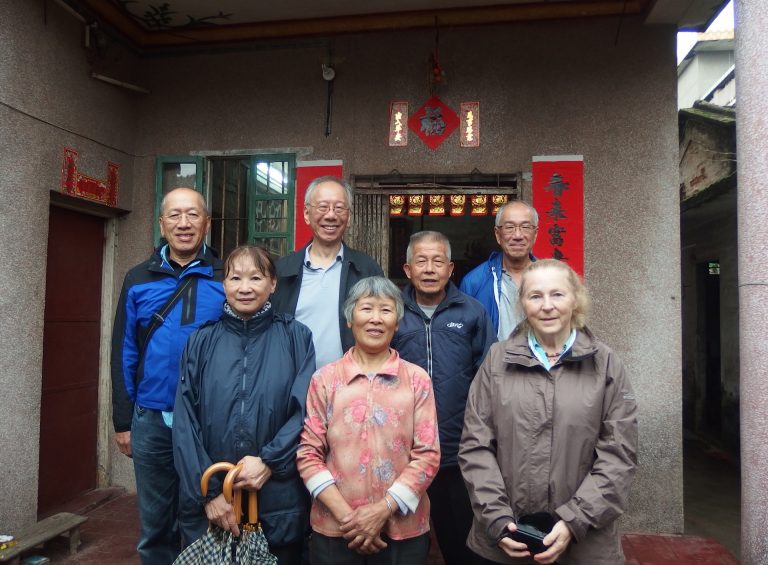

Some people travel long distances to perform tomb sweeping. Ying, research manager at My China Roots, travels from Guangzhou to her ancestral home in Fujian every year.

“The tombs are spread around the mountain behind our village, and the grass grows so high so that it’s impossible to make out the path. We’ve been relying on our neighbour to take us, but we worry about what will happen when he is too old to hike up the mountain. In our case, their isn’t actually any tomb-sweeping involved, because most of our ancestral tombs no longer have a headstone. For those that do, we carry red ink to help us make out the inscriptions.”

Ying, research manager at My China Roots

Celebrating Chinese-ness

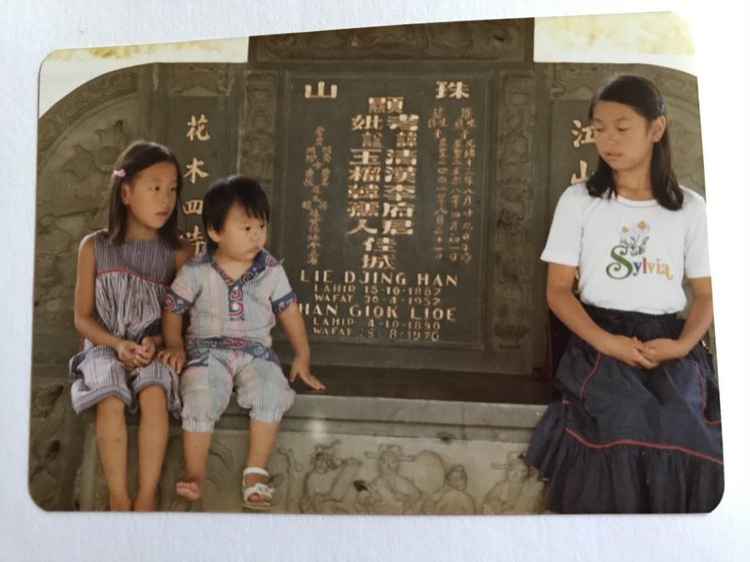

Outside of China, many Chinese communities have been able to practise Tomb Sweeping without being affected by the Cultural Revolution. Some rituals observed in Singapore and Malaysia, for example, date as far back as the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Abroad, tomb sweeping is often organized by clan associations. The Chinese Benevolent Association of Jamaica has organized what they call “Gah San” (the “adorning of the hills”) at the Kingston Chinese Cemetery for some 20 years. Every April, the association invites members of the Chinese Jamaican community to the Kingston Chinese cemetery for speeches, a banquet and burning of incense.

There is no denying the impact that this day has on the younger generation of overseas-born Chinese. For some, it is one of the few moments that they are exposed to their origins. My China Roots founder Huihan reminisces:

My grandmother passed away when I was around 6 years old. The fact that my mother would visit her grave at “Chingbing” (hokkien-dutch pronunciation) was one of the first instances where I became conscious of the fact that we were Chinese, or at least a bit different from my Dutch-countryside classmates. I still remember my mom’s little basket with a sponge, little rake, gardening gloves, and fresh flowers that she used to bring to the grave. We wouldn’t bring, burn or sacrifice any food, paper money or incense, just clean the graves and make sure it was cared for.

Huihan Lie, CEO of My China Roots

The Future of Ching Ming

In China’s cities, the resurgence of tomb sweeping is tied to a deeper anxiety: that of dwindling spaces in cemeteries. The increase in demand and shortage of space has spurred an exorbitant increase in plot prices, for burials and cremations alike.

There are also growing concerns about the environmental impact of Ching Ming. In 2021 – 1,300 years after Tang Xuanzong aimed to curb the out-of-control behaviours of his people – the Chinese government banned the burning of ghost money in several Chinese cities, sparking outrage throughout China.

Even before the pandemic, the government was advocating virtual grave-sweeping services. Jingwen is thankful that cemeteries are open again this year: “In 2020, the government banned tomb-sweeping because of COVID. We stayed at home while cemetery staff performed the rituals via livestream.”

As the meaning and rituals of Tomb Sweeping continue to evolve, one thing is certain: Ching Ming is as much about staying connected to the past, as it is about being rooted in the present – no matter how uncertain this present may be.

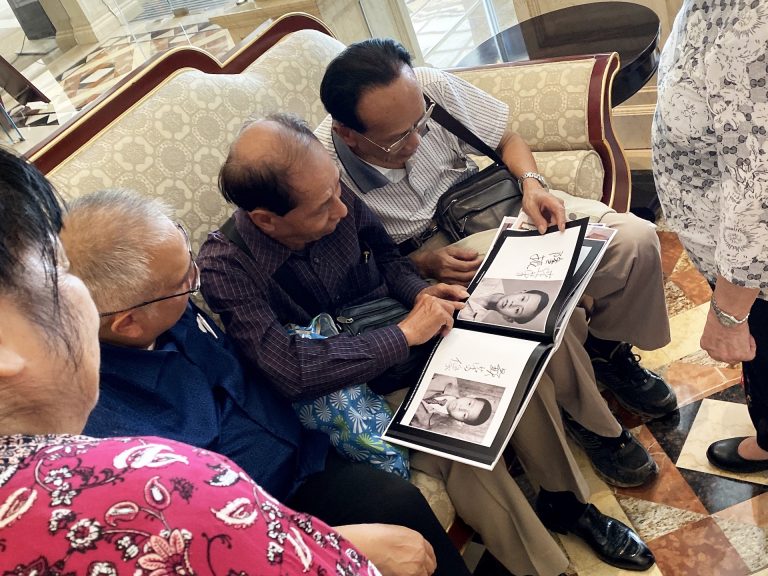

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!

Hi Clotilde, have not seen you in a few years. Hope it is well with you. Humbly yours, Karl Chung.