Foreword

“The Zhang Clan Odyssey” is the intimate pursuit by Raymond Douglas Chong (Zhang Weiming) at Gold Mountain (America) to discover his Zhang clan ancestral roots in Cathay (China).

Since January 30, 2003, after the suicide of John Thomas Killip in Monterey, California, the bamboo rod (American Born Chinese (ABC)) learns and grasps the epic saga of his Zhang forefathers in Cathay.

Since 2003, a mystical metamorphosis has enveloped Raymond Douglas Chong. Before, an American Born Chinese and professional engineer pursuing the American Dream in Gold Mountain. Now, a proud American with deep ties to China, while transmuting to writer, poet, and lyricist. He has discovered sad stories, huge legends, and dark secrets in Cathay.

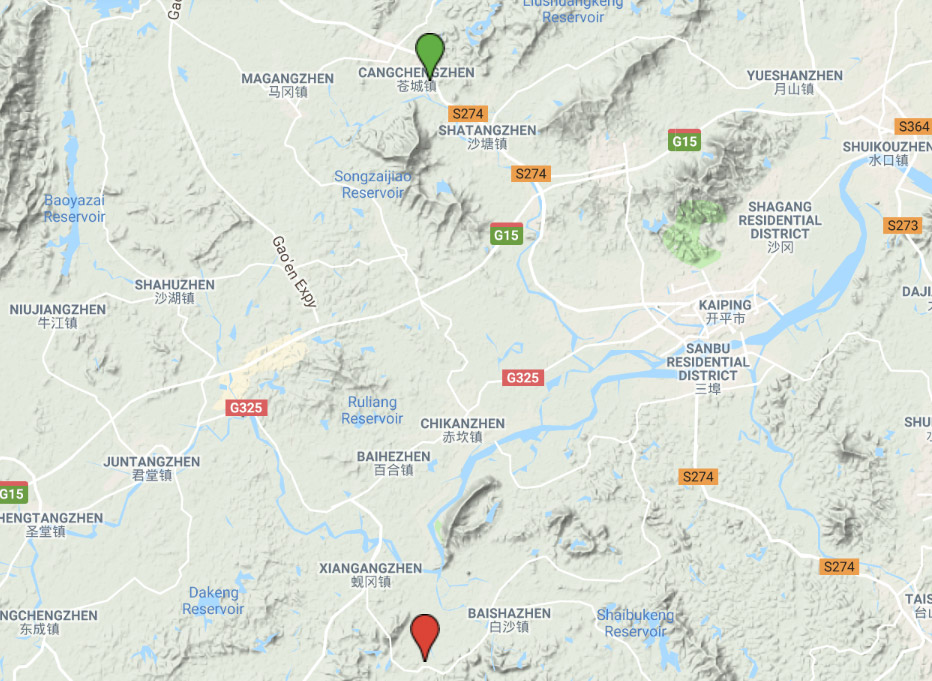

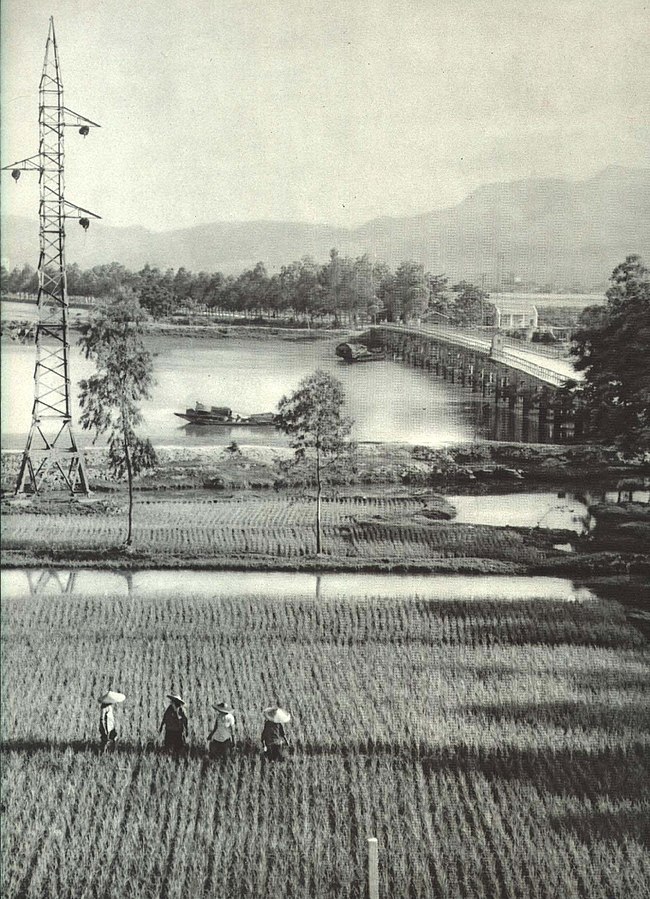

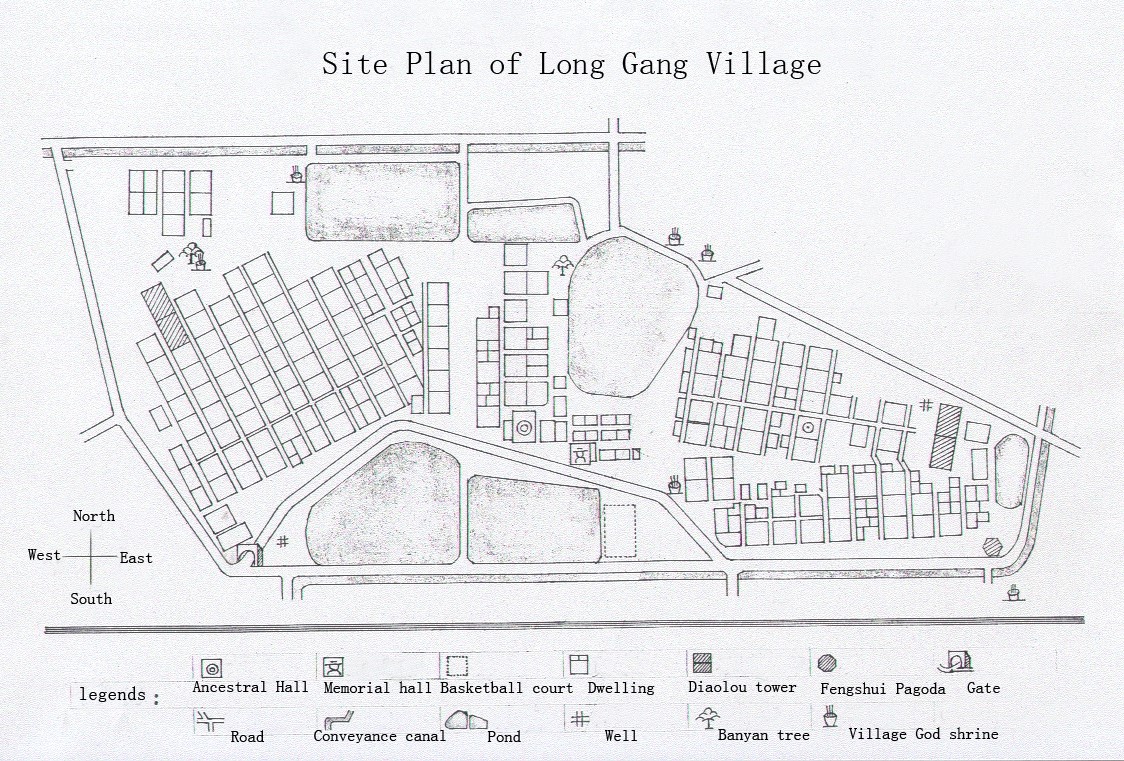

Its climax is the return of a fallen leaf (sojourner) from Gold Mountain to Yung Lew Gong (Long Gang Li) - Village of Dragon Hill, in Hoyping (Kaiping) - Land of Peace in Kongmoon (Jiangmen) City in Kwangtung (Guangdong Province) in Cathay. The mystical allure of the Yung Lew Gong with its Diaolou (stony watchtower) near Mountain of Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea along Tam Kiang (Tanjiang) river lures the heart and soul of a fallen leaf from Gold Mountain.

420-618 AD, Zhang Shouli and Junzheng: A Beginning

Birth of Zhang Shouli: The Tail End of Turmoil

Let us go back, way back. It is the second half of the sixth century AD, and China is in a continuous state of chaos and civil war. The once unified and powerful Chinese Empire has become a ravaged, divided, ragtag group of warring states and dynasties led by different ethnic groups. At the same time, culture and arts are flourishing, technology is advancing, and Buddhism and Daoism are gaining a foothold.

The era became known as the “Northern and Southern Dynasties,” which saw so much social unrest that an overwhelming number of Han Chinese migrated from the north to the lands just south of the Yangtze River (in today’s central China).

It may be that your great (x51) grandfather Zhang Shouli was among the many thousands forced to migrate south, as we know that at some point, he lived in the lands around the Yangtze River. More specifically, your first known ancestor Shouli lived in a place called Tushan in Zhongli prefecture, around today’s Fengyang county in Anhui province.1

While we do not know where Zhang Shouli was born, in 570, the timing of his birth would have been during the latter stages of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589 AD).2

Yangtze River

Yangtze River581 AD: The Sui Dynasty and a Unified China

The Sui Emperor

The Sui EmperorAround the time Zhang Shouli was a boy, possibly a young teenager, a bloody purge was taking place up north that brought a stop to centuries of chaos. In the Imperial Palace in the Empire’s capital of Chang’an (today’s Xi’an in Shaanxi province), the Duke of Sui had 59 princes of the royal family killed.

And so it was that in 581 AD, the duke proclaimed himself the first Emperor of the Sui Dynasty and cultivated a public persona known as the "Cultured Emperor." The new Emperor reunified Southern China – ruled by impromptu courts of aristocratic families who had fled there from the north – and Northern China, previously controlled by foreign rulers, thereby reinstalling the rule of ethnic Han Chinese to the entirety of China.

The Grand Canal

Zhang Shouli had three sons, the youngest of whom was your ancestor Zhang Junzheng. Junzheng was likely born around 600 AD, against the backdrop of a newly unified empire entering a golden age of prosperity. Agricultural surpluses supported rapid population growth and wide-ranging reforms and mega-construction projects were undertaken that still has impact on Chinese society 1400 years later.

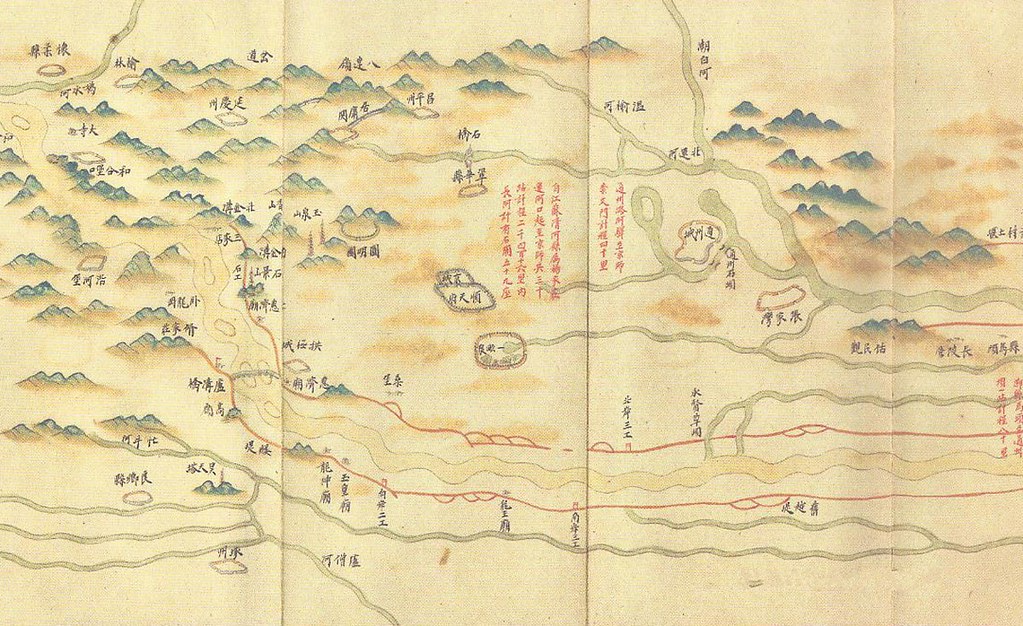

Living in Fangcheng in Fanyang (today’s Beijing, Tianjin and Baoding prefecture), Junzheng will have noticed at least one of these mega-construction projects while growing up: the building of the Grand Canal.3

The Grand Canal connected the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, the two most important rivers in China’s history. With the eastern capital of Luoyang at the center of the network, the Grand Canal linked the west-lying capital Chang'an (today’s Xi’an) to the economic and agricultural centers of the east towards Hangzhou, as well as to the northern border near modern Beijing, where your forefather Junzheng lived.

While the initial key goal of the Grand Canal was to ship grain to the capital and transport troops and military equipment, the canal was to facilitate domestic trade, the flow of people and cultural exchanges for over a millennium to come.

Ancient map of the Grand Canal

Ancient map of the Grand CanalFall of the Sui Dynasty

But the mega-construction projects, which in addition to the Grand Canal also included parts of the Great Wall, were about to take their toll. Financing the projects strained the economy, and many of the millions of conscripted construction workers died due to the harsh working conditions, angering a resentful workforce. Rural rebellions further drained the military, the agricultural sector, and thus the economy.

Zhang Junzheng will likely have been coming of age when he heard the news that the Sui Emperor had been assassinated by a group of his own advisors in 618.

And thus, a mere 37 years after its establishment, the Sui Dynasty fell, leaving a legacy that far surpassed its tenure, and paving the way for perhaps the most celebrated of all dynasties in Chinese history: The Tang Dynasty.

618-678 AD, Tang Dynasty: Junzheng Arrives in Guangdong

Junzheng Sows the Seeds for the Guangdong Zhang Clan

Zhang Junzheng was to build a successful career in government under the Tang rulers, who hailed from an aristocratic, northern Han Chinese family.

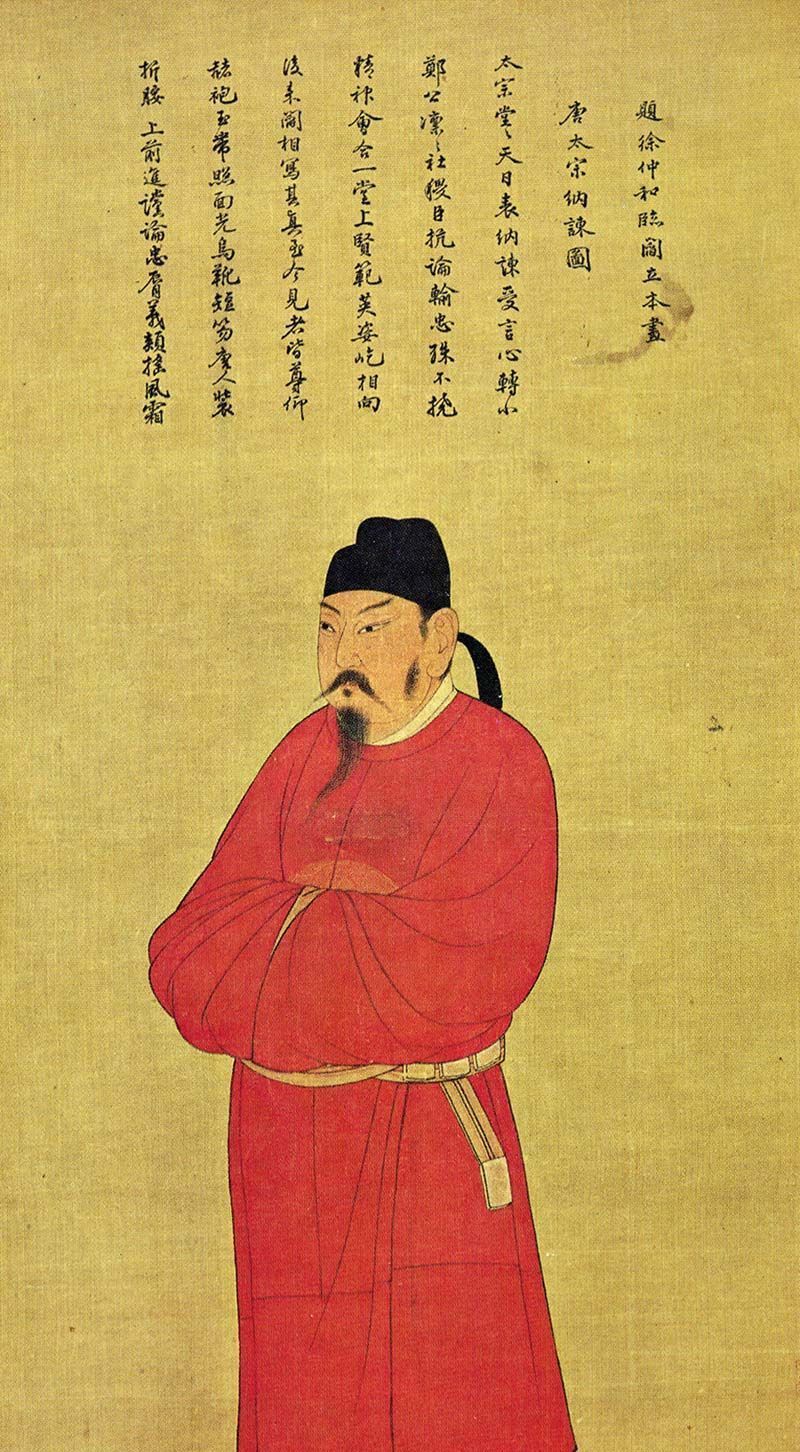

Your great (x50) grandfather Junzheng managed to climb his way up to become a vice-mayor, a position he obtained during the reign of Taizong, the second Tang Dynasty emperor, who ruled from 626 to 649 AD. The prefecture that Junzheng presided over was called Shaozhou and located in Guangdong province, a relatively remote area of the Tang empire at the time.

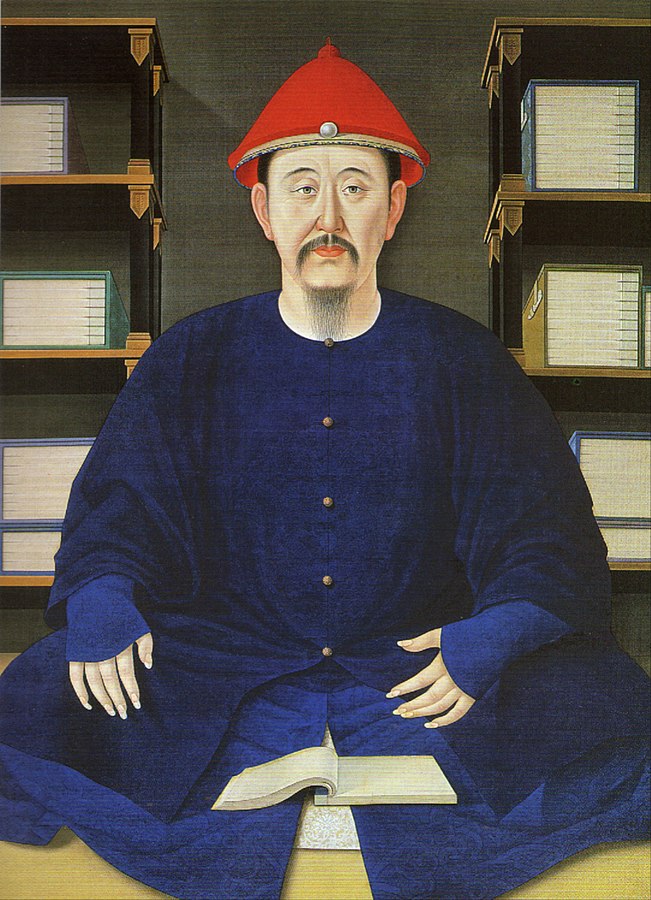

Emperor Taizong

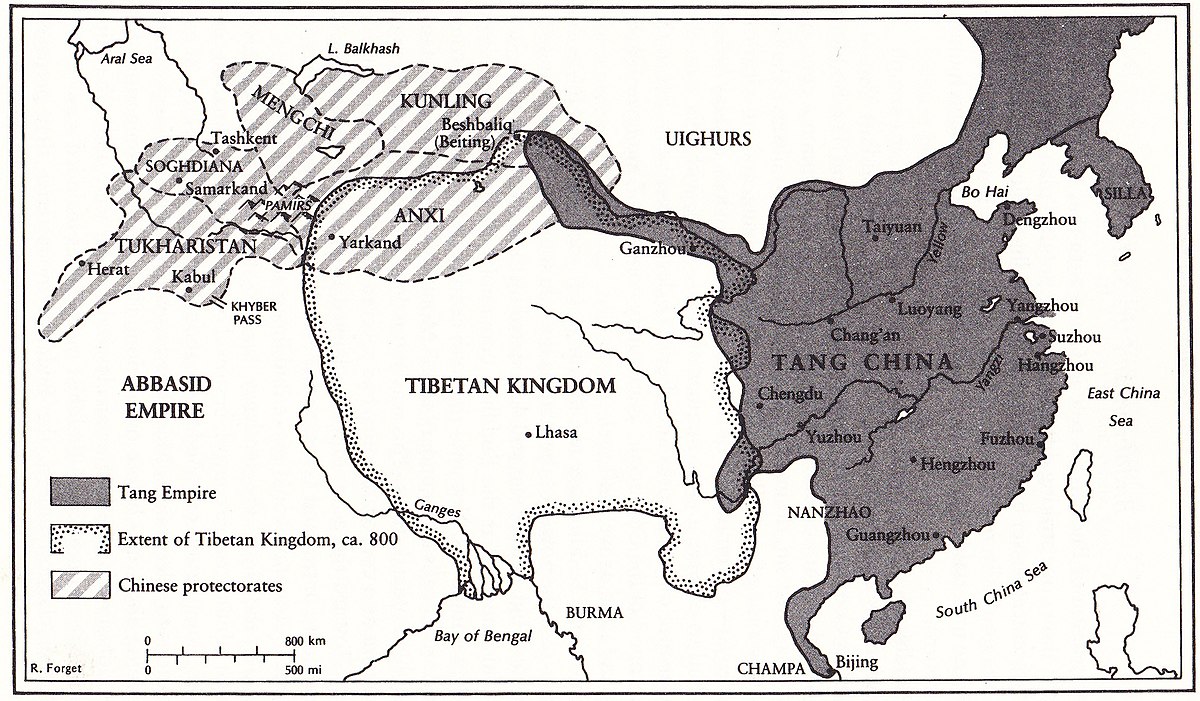

Taizong, whose reign lasted from 626-649 AD, is often seen as one of the greatest emperors in China's history. His reign became the model against which future emperors were measured and was literally treated as required study material for future crown princes. Under Taizong’s reign, China flourished economically and militarily, largely enjoying prosperity and peace across a territory stretching to today’s Vietnam in the south, and Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan in the west.

Uncommon for nobility at the time, Taizong was a rationalist who valued logic and scientific reason, openly scorning superstitions and claims of signs from the heavens.

Zhang Junzheng was your first Zhang ancestor to settle in Guangdong. The place he settled was in the northern part of the province, along the borders with Hunan and Jiangxi.

A vice-mayor of a prefecture (“zhou”) was a position of influence. China’s population at the time stood around 50 million people, and with a few 100 prefectures, one prefecture could easily count over 150,000 residents.4 Such a position did not just bring political influence, it brought wealth, employment, and considerable status for the extended family.

Shaozhou in Guangdong, which borders the provinces of Hunan and Jiangxi

Shaozhou in Guangdong, which borders the provinces of Hunan and JiangxiJunzheng died before he reached retirement. After his death, his descendants settled in Shaozhou (in today’s Qujiang district of Shaoguan city, Guangdong province).5

Zhang Zizhou: County Magistrate

Junzheng had six sons, the eldest of whom was your great (x49) grandfather, named Zhang Zizhou. Zizhou was likely born around a quarter into the 7th century, in the early stages of the Tang Dynasty and around the time Taizong ascended the throne.

Undoubtedly partly due to his father’s government position, Zizhou obtained the role of magistrate of Yueshan County (today’s Xinchang County, Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province). County magistrate was one administrative level lower than the (vice) mayor of a prefecture (or “zhou”).6

Administratively, counties were the most fundamental units of local government. To common villagers, the county magistrate was typically “the face” of government in general, as he was the lowest administrative leader that directly represented the Emperor – the Son of Heaven – himself.

Imperial Examinations

Imperial ExaminationsThe appointment of magistrates at times was a contest between the central bureaucracy, which represented the interests of the emperor, and local nobility and elites. Imperial representatives were typically scholar-officials who had gone through the rigorous Imperial Examinations and were selected largely on merit rather than birth (as was the case with the local aristocracy). During the Tang Dynasty, this contest was reduced in relevance as the "rule of avoidance" was increasingly observed. This rule forbade magistrates to serve in their home county because of the danger of nepotism and favoritism to family or friends. Magistrates could also only serve up to four years in one place before being transferred.

The magistrate's responsibilities were broad but not clearly defined. The county magistrate supervised units of control below the county level. These included village elders, local institutions, and self-ruling townships.

Zhang Hongyu and Jiuling: Like Father, Like Son

Zhang Zizhou had four sons; the eldest was called Hongyu.7 With his grandfather a prefectural vice-mayor and his father a county magistrate, Zhang Hongyu was born into a family of privilege. Growing up as a young man, he was unlikely to ever be worried about his prospects of finding work. Indeed, Hongyu found a perfectly good job as a minor government official in Suolu County in Xinzhou Prefecture (today’s Xinxing County, Yunfu, Guangdong Province).

It must have been in the second quarter of the 8th century, towards the end of his life, or perhaps even posthumously, that Hongyu was awarded the honorary title of Taichang Qing, which made him a “director of sacrificial worship.” Interestingly, he did not receive this title because of the achievements of either his father or grandfather, but instead thanks to the those of his oldest son Zhang Jiuling.

678-740 AD, Zhang Jiuling: Golden Age for China and Your Zhang Clan

Jiuling: Promising from the Start

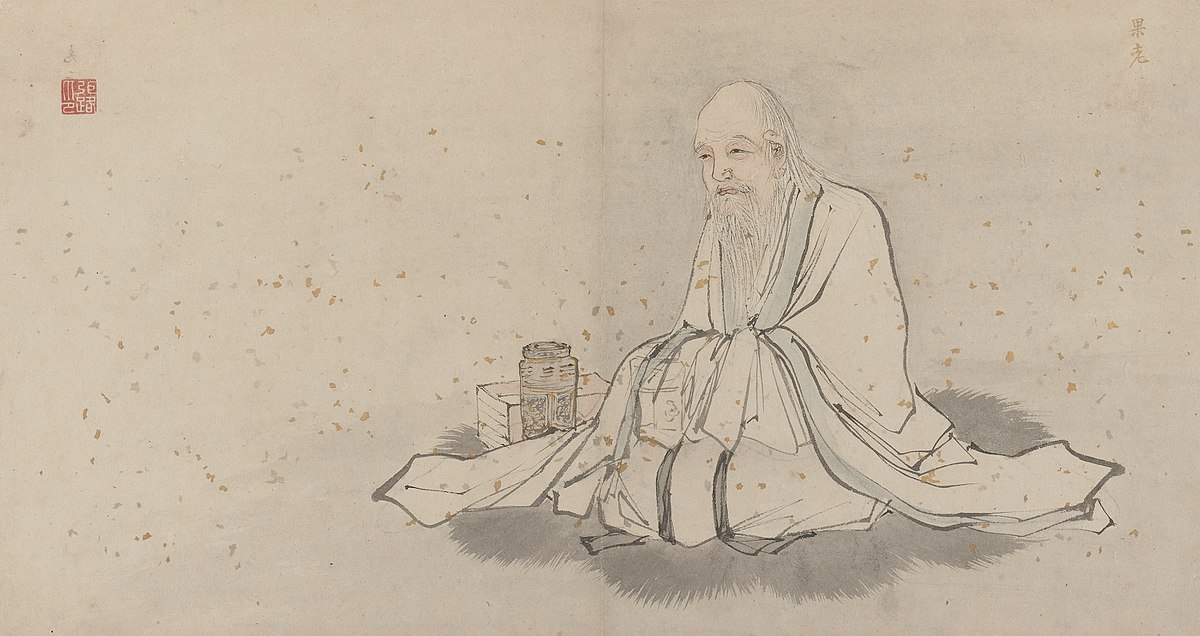

Zhang Jiuling

Zhang JiulingZhang Jiuling was born in 678 in Qujiang, Shao Prefecture, Guangdong. He had two younger brothers: Jiugao and Jiuzhang.8

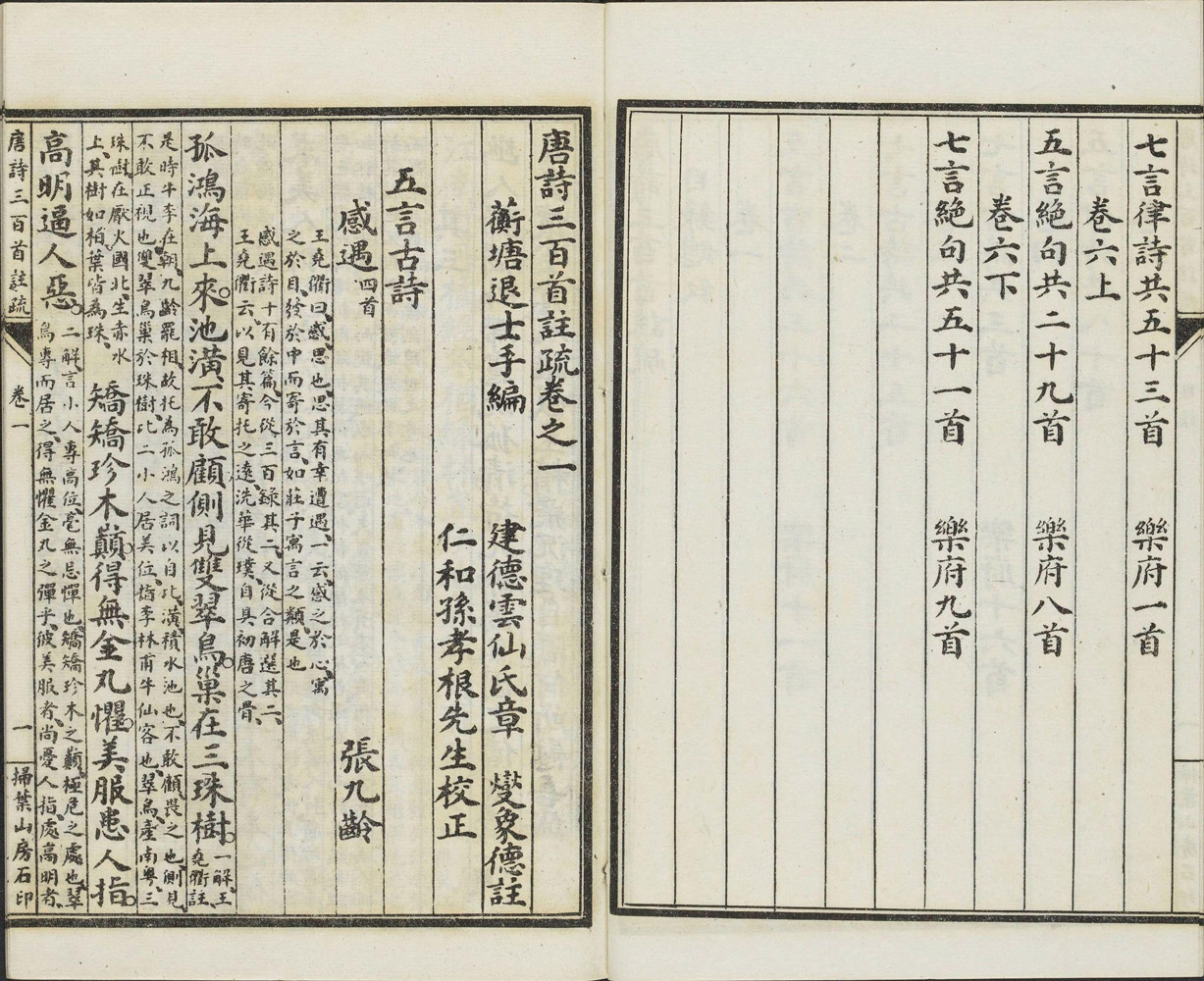

From an early age, Jiuling was exposed to scholar-officials, several of whom had publicly praised his intellect and literary talent. Later on, Jiuling passed the highly prestigious imperial examinations, which had become more prevalent during the Tang Dynasty, as a way to make the path toward becoming a scholar-official more merit-based, rather than custom for the aristocracy. Jiuling achieved the highest possible score in the examinations.

Jiuling became known for his exceptional skills in seeing through people’s characters and spotting their talents. In the first decades of the 8th century, he rose quickly through the government ranks, up to the point that the Xuanzong Emperor appointed him as one of the key officials at the highest level to assign postings to civil servants.

Your great (x47) grandfather married Ms. Tan, and was on his way to becoming a prominent minister, noted poet and scholar of a Tang Dynasty that was at the height of its magnificence. The world was at his feet.

Imperial Examinations

The Imperial Examinations were the doorway to political, social and economic success throughout much of China’s history. The system was designed to select men for government service according to intellectual merit rather than ancestry or wealth.

The examinations themselves were free and open to all adult Chinese males. However, taking the examinations was costly due to the travel and lodging costs, and years’ worth of study, during which the relevant son could not work to make money for the household. As the social and economic success would be shared with the wider family, rural sub-clans often collectively financed the education of its most promising young talent.

A poem by Zhang Jiuling in the famous anthology *Three Hundred Tang Poems*

A poem by Zhang Jiuling in the famous anthology *Three Hundred Tang Poems*The Tang Dynasty in All Its Glory

Known as a "Chinese Mona Lisa," the largest Buddha statue at the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang was supposedly carved in the image of Empress Wu.

Known as a "Chinese Mona Lisa," the largest Buddha statue at the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang was supposedly carved in the image of Empress Wu.Cosmopolitan, dynamic, expansive: All adjectives commonly attributed to the Tang Dynasty today. In reality, it was only the first half, i.e. the first 150 years, that gave the Tang Dynasty that reputation. In that period, China saw vast territorial expansion and increase in international and interregional trade. It was the golden age of Chinese poetry and cultural flowering. The Tang capital of Chang’an (today known as Xi’an) grew to be the largest city in the world, attracting traders, students and pilgrims from all over Asia. Buddhism became a major influence in Chinese culture. The high point of Tang culture came in the first half of the 8th century under Emperor Xuanzong, the grandson of Empress Wu. A fan and patron of poetry, music and the arts, he also invited Daoist and Buddhist clerics to perform rituals in court to aid the victory of Tang forces and avert drought.

Emperor Xuanzong

His reign was the longest among all Tang Emperors, lasting from 713 to 756 AD. In the first half of his reign, he brought China to the pinnacle of culture and power. Politically, he increased government efficiency, reduced corruption, raised officials’ accountability, and improved mechanisms to appoint and remove county magistrates. Economically, he shifted land ownership from local governments to peasants, allowing farmers to buy and sell their own land.

The second half of his reign, however, showed the opposite picture: a self-indulgent, careless ruler, who set in motion the start of the decline of the mighty Tang Dynasty.

Empress Wu Zetian

The Tang Dynasty was briefly interrupted by an unlikely foe: Empress Wu Zetian (a woman!) seized the throne in 690, and ruled the Zhou dynasty for 15 years. The concubine of the second Tang emperor, Taizong, she was the only officially recognized reigning Empress in the history of China. Learn more.

Zhang Jiuling and Filial Piety

He also built a reputation for his filial piety. In 726, he requested to be posted to a prefecture south of the Yangtze River, so that he could be closer to his ill mother in Shao Prefecture. Emperor Xuanzong not only granted his request by making him a prefecture commandant in modern day Nanchang in Jiangxi province, he also issued an edict praising Jiuling for his filial piety. Moreover, Emperor Xuanzong also made his brothers Jiuzhang and Jiugao prefects in the region, so that all three sons could visit their mother regularly. In 732, Jiuling’s mother died, and he returned to Shao Prefecture to observe a period of mourning.

Chancellor!

The next year however, his mourning period was cut short as Jiuling was appointed Chancellor to the Emperor, one of the very highest positions in the Tang Dynasty civil service. One characteristic that negatively impacted his reputation was that he was impatient and easily angered. On the other hand, Jiuling was also said to be honest and always seeking to correct the emperor's behavior, even if it offended the emperor.

Zhang Jiuling vs. An Lushan

In 736, Jiuling recommended that the Emperor Xuanzong execute a talented, rising military star named An Lushan. An had publicly disobeyed an order by a superior, and Jiuling was fearing a bad precedent would be set unless the Emperor acted decisively. Moreover, Jiuling felt strongly that An had the temperament to commit treason and would surely do so in the future. However, Emperor Xuanzong was too impressed by An's military talent and essentially pardoned him.

An Lushan

An LushanJiuling moved to Huxi Township, staying within his ancestral county of Qujiang in today’s Shaoguan, Guangdong province.9 He died in 740 at the age of 62, while on a vacation in Shao Prefecture to visit his parents' tomb.

16 years later in 756, the An Lushan Rebellion shook the Tang Dynasty, and Emperor Xuanzong was forced to flee south to modern Sichuan and Chongqing. Remembering Jiuling's warning about An, he issued an edict posthumously honoring your great (x47) grandfather and sent messengers to Shao Prefecture to offer him sacrifices.

An Lushan Rebellion (755-763 AD)

An Lushan was a Tang military general of Turkic origin who rose to power in part thanks to his (likely romantic) relationship with Emperor Xuanzong’s favorite concubine: Yang Guifei. In 755 AD, An Lushan turned against the emperor and marched his troops to the capital of Chang’an (today's Xi'an). Forced to flee, Xuanzong first executed his beloved consort Yang Guifei and, overcome with grief, abdicated upon his arrival in Sichuan.

An Lushan declared himself Emperor and established a new Yan Dynasty, which ended a mere seven years later due to internal dissent. The Tang Dynasty would never truly recover its prior cosmopolitan empire.

8th Century (2nd Half), Zhang Zheng to Dunqing: Tail End of Tang Heyday

Zhang Zheng: Senior Imperial Scapegoat

Zhang Jiuling had two sons: Zhang Zheng and Zhang Ting.10

Zheng developed a reputation for being righteous and never afraid to stand up for what he believed was right, no matter how powerful his counterpart. He was a type of counselor or “reading partner” of the Tang crown prince. His responsibilities were to study alongside the prince as a supporting party to help the prince out. Interestingly, his role also included receiving the teacher’s blows and punishment in instances where those were actually meant for the crown prince. As the crown prince was expected to become emperor, teachers were not able or allowed to punish the crown prince directly, and Zheng was thus a senior-level imperial scapegoat.11

He married Ms. Qiu and they had two sons: Zhang Cangqi and Zhang Guoqi.12

Zhang Cangqi

Zhang Cangqi was born around the turn of the 8th century and was also known as Daxue. Like his father and grandfather, he obtained an official role at the Imperial Palace. His title was that of Huangmen Shilang, i.e. officer at the palace, and later he was promoted to the position of Minister of Public Works, which put him in charge of national water conservancy and civil engineering, transportation, as well as government and industrial works.13

Zhang Dunqing: Father of Four Very Successful Sons

Zhang Cangqi had one son named Zhang Dunqing. Dunqing may well have been one of the proudest fathers in your entire Longgangli Zhang lineage, with all his four sons becoming very high level government officials in the heart of the all-powerful and cultured Tang Dynasty, around the second half of the 8th century.

Dunqing also had achievements of his own to be proud of. In good family tradition, Dunqing became a government official, and he gradually climbed his way up to become a Dianzhong Shiyushi or censor.14 The Censorate of the Tang empire consisted of three departments: The Headquarters Bureau, the Investigation Bureau, and the Palace Bureau.

The Headquarters Bureau controlled the state officials, interrogated criminals, and supervised the capital granaries and parts of the Imperial Treasury. The Investigation Bureau controlled the empire’s officials and inspected the provinces, prefectures and districts. They also managed all forms of punishment and jails.

Dunqing however, worked for the Palace Bureau, where he was one of the nine palace censors managing the Bureau, and supervising the arrangement of the officials, the imperial emblems and insignia during court audiences. Dunqing’s Palace Bureau also oversaw the police forces inside the capital of Chang’an, responsible for law and order on the streets and the markets of the capital.

Lishi Is A Zhuangyuan!

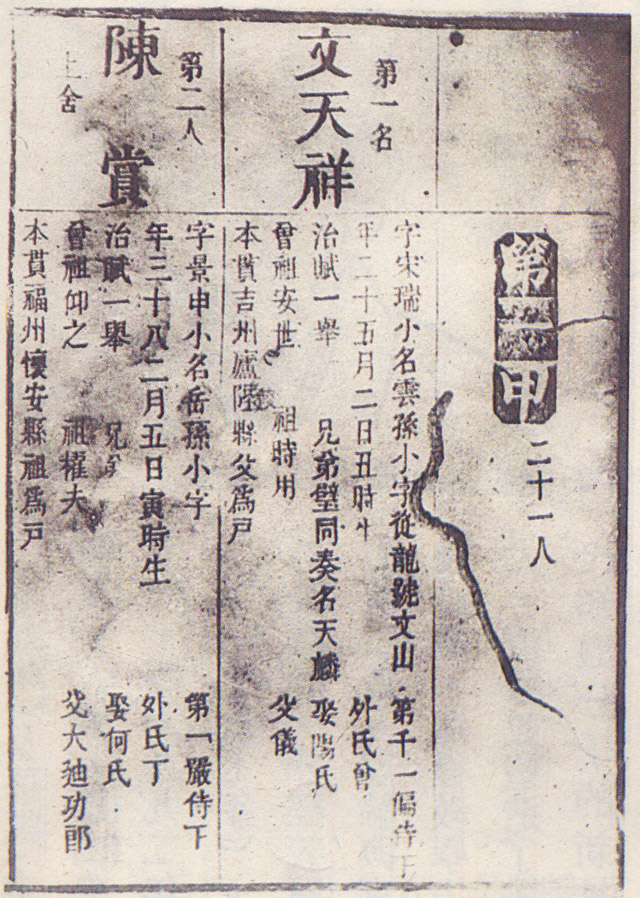

Ranking list of the *jinshi* examination

Ranking list of the *jinshi* examinationDunqing had four sons, of which the eldest was named Lishi (also known as Zhang Shao). We can say with reasonable certainty that one of the proudest moments in Dunqing’s life came when he heard the news that his son Lishi had achieved the first rank in the highest possible round of the Imperial Examinations, earning Lishi the prestigious title of Zhuangyuan.

Over the course of the Tang dynasty, the Imperial Examination system had developed into a more rigorous and more comprehensive system, moving beyond the former basic selection process of testing candidates on questions on policy matters followed by an interview.

By the time Lishi was taking the Examinations, the system had added written tests on mathematics, law, and calligraphy, exercises where candidates were given random sections of the Confucian classics with blanks that had to be filled in, and candidates had to compose original poetry on the spot, with very specific requirements.

The Examinations had different levels and different rounds. The highest possible round of the Examinations was the jinshi round. The success rate for candidates that participated in this ultimate round was only between one and two percent. Over the course of the Tang dynasty, an average of only about 23 jinshi degrees were awarded each year, for the entire empire. For of each jinshi round, the one candidate with the very best score would obtain the title of Zhuangyuan.

Imagine the look on Dunqing’s face when he learned that his son was a Zhuangyuan! Later, Lishi became a tutor at the Imperial Palace, personally responsible for educating members of the Royal Household.

Late 8th Century: Start of the Zhujixiang, Nanxiong Chapter

Zhang Gang: Your First Ancestor in Zhujixiang, Nanxiong

Zhang Dunqing had three other sons, of whom he had every reason to be proud of too.

His second son, your great (x43) grandfather Zhang Gang, was also known as Zhang Liying. Liying became provincial governor of Jizhou (today’s Ji’an City in Jiangxi province). Liying is of interest for your family history as he was the first one to settle in what was later called Zhujixiang, Nanxiong, Guangdong province. Nanxiong is in the far northern region of Guangdong, at the border with Jiangxi province; Nanxiong is also next to Shaozhou, the area where Zhang Gang’s preceding seven generations lived and your ancestor Zhang Junzheng had settled.

Dunqing’s third son Zhang Hai, a.k.a. Lihua, worked as Gongbu Shangshu or Minister of the Board of Works. The fourth son, Zhang Ji or Liwen was as provincial commander-in-chief of Zhejiang.15

Lined with plum trees, the ancient Plum Pass (Meiguan) in Zhujixiang served as the only northern migration route out of Guangdong province.

Lined with plum trees, the ancient Plum Pass (Meiguan) in Zhujixiang served as the only northern migration route out of Guangdong province.Zhang Dai

Zhang Gang had only one son and his name was Zhang Dai. Dai was born roughly half way into the 8th century, and worked at the Palace Secretariat, one of the main ministries of the Imperial government.

The key responsibility of the Palace Secretariat was to read incoming memorials to the Emperor, to answer his questions, and to draft his replies in the form of Imperial Edicts. It also was tasked to ask critical questions in cases that were difficult for the Emperor to decide. The Secretarial administration supervised the transfer of documents inside the palace and the summoning of state officials to be interviewed.16

Dai married Ms. Zhong, and they had two sons: the eldest was named Yan and the youngest Xing.

Zhang Xing

The second son Zhang Xing obtained the title of Chaojie Qing Dafu, which carried the fifth official rank (out of nine) in the Tang Dynasty government hierarchy. In ancient China, “Dafu”, often translated as “grand master”, were leading, powerful administrators, high up the Imperial hierarchy. However, during much of the Tang Dynasty, the title had become less functional and it did not seem to have given Zhang Dai any specific role or sphere of influence. On the other hand, this did not mean that titles had become merely symbolic: they secured a salary, as well as taxation and retirement benefits. Moreover, Chaojie Qing Dafu were allowed to see the Emperor in the autumn.17

Zhang Xing married Ms. Zhou, and they had one son, named Zhang Zhe, the first ancestor that is listed in your Longgangli Zhang Clan zupu.

The Jiupin Ranking System of China’s Bureaucracy

There were nine key levels that applied to the ranking of government officials and titles. If a man had both a position and a title, it was not necessarily the case that they were of the same rank.

Except for the very highest rank (rank 1), all ranks had sub-divisions. Ranks 2 and 3 both had 2 sub-levels, while ranks 4 to 9 all have 4 sub-levels. This meant that in total there were 29 sub-levels divided over 9 ranks.

For instance with respect to positions: a judicial officer at the county level was rank nine; the county magistrate was rank seven; and the prime minister and key ministers were at the very highest level, one.

Titles, Degrees, and Government Positions

There were titles (Chaoqing Dafu, Wenlinlang, Dengshilang etc.), academic degrees and designations (e.g. jinshi, tanhua), and government positions (e.g. governor, jiedushi, prime minister).

While theoretically, there was a link between these three concepts, in practice, they often functioned independently from one another. Most men with government positions also had titles, especially those with mid-to-higher level positions, and the majority of men with government positions had an academic degree.

On the other hand, there were countless men with titles (honorary titles, hereditary titles) who did not have a government position or academic degree. Titles could be awarded for a wide variety of reasons: some had titles because their father had a title, others received a title after obtaining a government position; some were awarded titles for exemplary contributions to society, others simply bought their titles. Judging from a title itself, it was not possible to see whether that person also held a government position or an academic degree.

Starting with the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the importance of the aristocracy in government began to decline, a process that continued into the Song Dynasty. This process was directly linked to the increasing importance of the Imperial Exams during these same two dynasties, which aimed to make the government system more meritocratic.

However, up until the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), titles remained crucial, as salaries and benefits such as retirement and taxation arrangements were based on title rather than position. Only from the Ming Dynasty onwards, benefits and salaries were based on positions.

9th Century (1st Half), Zhang Zhe: Common Ancestor of Three Clans

Zhang Zhe is the very first and earliest ancestor listed in your Longgangli Zhang Clan zupu.18 He is honored as the common ancestor of three related Kaiping Zhang Clan branches. These three branches are based in today’s Longgangli, Wapiankeng and Chakeng, and are referred to as the Shafu, Zhangqiao, and Shagang Zhang Clan branches.19

Your great (x40) grandfather Zhang Zhe was born around 770-780 and lived in Jingzong in Nanxiong, Guangdong. His courtesy name was Huayao.20

The Tang Dynasty was still in the process of picking itself up from the ground and dusting off the dark grey ashes from the An Lushan Rebellion. Throughout his childhood, Zhang Zhe would have seen the Tang struggle to regain its reputation and influence.

Backdrop: The Jiedushi vs. the Emperor

However, the strong central Tang control from the olden days had gone, and regional military governors known as Jiedushi21 were now largely the ones with power on the ground. The Jiedushi pretty much acted like rulers of their own independent states: they paid no taxes, named their own subordinates, and passed power to their own heirs.

In 805, three years before Zhang Zhe was to take the notorious Imperial Exams, he saw the last great ambitious Tang emperor come to power: Emperor Xianzong of Tang. Emperor Xianzong made it his mission to curb the powers of the jiedushi, and after several campaigns in Sichuan and Shaanxi to defeat those that did not obey him, he brought the whole Empire back under imperial authority. This period was also known as the Yuanhe Restoration.

Zhang Zhe’s Career

After being awarded a Jinshi in 808, Zhang Zhe was soon after promoted to the Palace Secretariat, where his grandfather Zhang Dai had worked before him. As a Secretary, Zhang Zhe would have handled many court documents relevant to the empire, likely including documents pertaining to Xianzong’s many military campaigns across the Empire. Zhang Zhe may also have contributed to the drafting of Imperial Edicts.

After the Palace Secretariat, Zhang Zhe served as Investigating Censor, whose duty was to check on all officials across the Empire and to inspect the various provinces, prefectures and districts. As an Investigating Censor, Zhang Zhe may also have managed issues related to punishment and jail time within his jurisdiction.

Of interest was that Zhang Zhe’s posting as Investigating Censor was in Fanyang (Beijing, Baoding and Tianjin).22 It is unclear whether Zhang Zhe knew that his own great (x8) grandfather Zhang Junzheng had also lived there, before the latter settled in the south and became the first ancestor in Guangdong.

Zhang Zhe’s Retirement and Resting Place

Kaiping (red), Shaoguan (green), Nanxiong (yellow)

Kaiping (red), Shaoguan (green), Nanxiong (yellow)Keeping the ancestral base in Jingzong, Nanxiong, in northern Guangdong, where his great-grandfather Zhang Gang had settled, Zhang Zhe moved to a different village, called Shashuitou Village, Jingzong Li, Shixing County, Nanxiong.23

Near the end of his life, Zhang Zhe was awarded the honorary title of Jishizhong, of the fifth rank, for his loyalty and service to the emperor. Zhang Zhe and his wife were buried together on Jinji Mountain, Wengyuan County, Shaozhou (today's Shaoguan, Guangdong Province).24

China’s Shakespeare’s Niece

The poet Han Yu

The poet Han YuZhang Zhe’s wife was the niece of Han Yu / 韩愈 (768–824), a famous writer, poet and government official. Also known as China’s Shakespeare, Dante, or Goethe, it is probable that the renowned poet and your ancestor met in the capital, when they were both serving as government officials.

Incidentally, Han Yu was a puritan Confucian staunchly opposed to official patronage of Buddhism. He was also famously outspoken, so when Emperor Xianzong accompanied what was alleged to be Gautama Buddha’s finger bone from a temple in Shaanxi to the imperial palace in grand pomp and circumstance, Han Yu vehemently spoke out against it. When he was exiled to Chaozhou, he wrote the most exquisite lines of poetry.

《晚春》

草木知春不久归, 百般红紫斗芳菲。 杨花榆荚无才思, 惟解漫天作雪飞。

Late Spring

The plants know that spring will soon return, All sorts of reds and purples compete in beauty. The poplar blossoms and elm seeds are without beauty, They can only fill the skies with flight like snowflakes.

Zhang Xing's New Name for Jingzong: Zhujixiang

Zhang Xing was Zhang Zhe’s only son and was born around the turn of the 9th century. At some point in the early 800s, perhaps while Zhang Zhe was occupied with government affairs in the north, Xing moved nearby Jiaoyi Gate on Jingzong alley in Nanxiong. For the seven generations that followed, his descendants and their families would call this place ‘home’.25

In 825, Emperor Jingzong of the Tang Dynasty heard of Xing’s impeccable morals and filial piety. To reward him, he gave him a ring made of pearls and precious stones.

Incidentally, the name of the alley they had been living on, ‘Jingzong’, was identical to the emperor’s name. To avoid the naming taboo that strictly forbade individuals from using the emperor’s given name, they changed the name to Zhujixiang or Zhuji Alley, literally ‘pearl jewel alley’.26

9th Century (2nd Half): Declining Tang Signals Upcoming Change

Tang Decline Picks Up Where It Left Off

Mural of eunuchs from a royal tomb in Qianling, Shaanxi

Mural of eunuchs from a royal tomb in Qianling, ShaanxiUnfortunately, after Emperor Xianzong managed to briefly re-establish and stabilize Tang rule over the whole empire, his successors proved less capable, and the Tang decline that had started in the second half of the 8th century continued. The Imperial Court put the palace eunuchs in charge of the palace army, which had been created to counter the eventual threat of mutinous regional commanders. Before long, the eunuchs took control of palace affairs, and court politics in the 820s revolved around plotting the enthroning, murdering or coercing of one emperor after the next.

Zhang Xing will have started to reach middle age when in 835, a bloodbath occurred up north in the West Market in the Tang capital of Chang’an. The Jingzong Emperor’s successor, his younger brother Wenzong, had attempted to overthrow several key eunuchs. Wenzong’s plot was discovered and in retaliation, the eunuchs ordered the immediate and public execution of 1000 officials and allies to the emperor.27

Meanwhile, there were external pressures on the Tang’s borders. In 848, military general Zhang Yichao 28 took advantage of the Tibetan empire’s civil war to take it over. The Turkic Uighurs, on the other hand, had helped quash the An Lushan rebellion but demanded huge quantities of silk in exchange, or they threatened to raid the capital of Luoyang. Already struggling to maintain control of their current territories, the Tang decided not to attempt the recovery of their past territories of Central Asia.

The Tang empire and surrounding kingdoms, ca. 800 A.D.

The Tang empire and surrounding kingdoms, ca. 800 A.D.Zhang Tingze and Zhang Ku: A Final Straw, the Huang Chao Rebellion

Map of the Lingnan circuit and other administrative regions of the Tang Dynasty

Map of the Lingnan circuit and other administrative regions of the Tang DynastyA decade or so later, Zhang Xing’s great-grandson and your great (x36) grandfather Zhang Tingze was born in Nanxiong, Guangdong, followed by his brothers Tingfan and Tingyan.29

After the An Lushan Rebellion, the weakened Tang Empire remained plagued by internal uprisings. The one that led to the eventual Tang disintegration was started by a well-educated salt smuggler, who gave his name to the uprising: the Huang Chao Rebellion (874–884). Following a series of droughts, floods and famine, Huang Chao raised an army against Tang Emperor Xizong.

Back in Nanxiong, Guangdong, in the middle of the rebellion, in 877, Zhang Tingze’s only son was born. His son was named Zhang Ku. The next year, in 878, Huang Chao marched all the way south to Lingnan and laid siege to the circuit’s capital Guangzhou, some 300 km south of Nanxiong, where Zhang Tingze and Zhang Ku were living. Three years later, Huang Chao captured the Tang capital of Chang’an in 881 A.D., proclaiming himself Emperor of the new Kingdom of Qi.

Shortly after, Huang Chao was killed by his nephew, ending Huang’s kingdom in 884 A.D. Nominally, the Tang were still in power.

Lingnan / Nanyue

During the Tang dynasty, the empire was divided into circuits / 道, or provinces. Lingnan circuit in the south encompassed all of Guangdong province, Fujian province, Hainan island, Guangxi province, the southeast of Yunnan province, and the northern section of Vietnam. Lingnan circuit’s capital was Guangzhou.

The Lingnang name means literally “south of the Ling Mountains”, a major mountain range straddling Guangxi, Guangdong and Hunan. However, this entire area used to be known as “Nanyue” / 南越, an ancient kingdom established in 204 B.C. and vassal state to the Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.). Although founded by leaders from the Chinese heartland, the inhabitants of Nanyue were mostly non-Chinese Yue hill tribes, who were eventually assimilated into the Chinese empire.

The name "Vietnam" is derived from Nam Việt, the Vietnamese pronunciation of Nanyue.

Zhang Ku Orphaned and Raised By Uncle Zhang Tingfan

By the time the Huang Chao Rebellion had officially ended, Zhang Ku was seven years old, and his father Zhang Tingze had likely already passed away.30 Fortunately for the orphaned, brother-less Zhang Ku, his uncle Zhang Tingfan brought him in and took him under his wings.

Zhang Tingfan was a high level official, serving the Tang Emperor as a Yuyingshi, a military Commissioner of the Imperial Encampment, in charge of troops when an emperor personally undertook military campaigns.31

In 905, Tingfan switched positions and was appointed a senior role at the Changpingsi of the Stabilization Fund Bureau of Lingnan Circuit:32 a position of the seventh official rank, which consisted primarily of supervising the local granary, building up grain reserves to stabilize grain prices and support undeveloped regions in cases of famine.

907 AD: The Tang Falls, Zhang Ku and Tingfan Flee to Szeyap

Leaving Zhujixiang: Southward to Szeyap

The Khitan Liao Empire (907-1125)

The Khitan were a nomadic people that ruled a vast territory encompassing parts of modern-day Mongolia, Northern China, Russia, and Northern Korea. Founded around the collapse of the Tang, the Liao Empire was for a long-time seen as the ever-powerful northern neighbour, and not even the Song were able to dislodge it from the area around Beijing. The Jurchens, a herding, farming, hunting people based in Manchuria, eventually toppled them in 1125.

Khitan’s cultural and government system was vastly different from that of the Chinese. The Khitan promoted a more egalitarian society, in which women could hunt, manage property, and hold military posts.

The Liao Dynasty, ca. 1000 A.D.

The Liao Dynasty, ca. 1000 A.D.However, two years later, the lives of Zhang Ku and his uncle Tingfan were turned upside down. In 907, after a long period of gradual decline, the inevitable happened: The Tang Dynasty had officially fallen.

Despite having technically defeated the Huang Chao Rebellion in 884, the Tang Dynasty was left severely weakened and vulnerable to attacks. Huang Chao’s defeat had been made possible thanks to a jiedushi called Zhu Wen, who initially served as a general in Huang Chao’s armies but later switched allegiance to the Tang. To reward him for his timely defection, Tang Emperor Xizong had appointed him Grand General of the Imperial Guards, and Zhu Wen subsequently led several campaigns against Huang Chao and his allies.

Emperor Zhu Wen of the Later Liang

Emperor Zhu Wen of the Later LiangHowever, following the end of the rebellion, Zhu Wen continued to amass power, and by 907, he had enough authority and mliilitary backing to storm the Imperial Court at Luoyang, where the last emperor of the Tang dynasty had taken refuge. Zhu Wen proclaimed himself Emperor of the Later Liang Dynasty (907-923) and ushered in the era of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Back in Nanxiong, the official end of the Tang Dynasty meant problems for your Zhang ancestors, whose prominent position in society was heavily linked to the Tang rulers. Zhang Ku, by then 30 years of age, and his uncle Tingfan saw no other option than to flee to a place further south and further removed from the new power center in the north. They decided to move to Jinzixiang Hanwuqiao in Gugangzhou, today’s Xinhui County in Szeyap, Guangdong province.33

The Nanxiong–Zhujixiang Legend

Today, countless of Guangdong clans claim that their ancestry came from Nanxiong before settling down in Guangdong’s heartland or coastal regions. The origins of this claim is one of the most famous legends in Cantonese tradition. This tale of Zhujixiang clans spreading across Guangdong takes place around the end of the Song dynasty, some 2.5 centuries after your own ancestor Zhang Ku fled Zhujixiang with his uncle Zhang Tingfan.

It was likely in the year 1273, that an imperial concubine named Su fled the Imperial Palace after having incurred the wrath of the Emperor. She met a wealthy merchant, who fell in love with her beauty and took her back with him to his home in Nanxiong in northern Guangdong.

When the emperor discovered the concubine's absence, he ordered an empire-wide search for her. A disgruntled former servant of the merchant informed the authorities of the concubine’s whereabouts and military troops were dispatched to not only kill the concubine, but all of the local Nanxiong population.

News of the approaching military went like shockwaves through Nanxiong and 97 family Zhujixiang families fled south settling in the then undeveloped Pearl River Delta, where their descendants still live today.

Some historians have argued that a more plausible explanation of the large population growth around the time of the Song-Yuan Dynasty transition is that the invading, northern Mongol armies caused a massive southward migration flow, and for all the refugees coming from the north, Nanxiong was the key hub to reach the safety of southern Guangdong’s heartland and coastal areas.

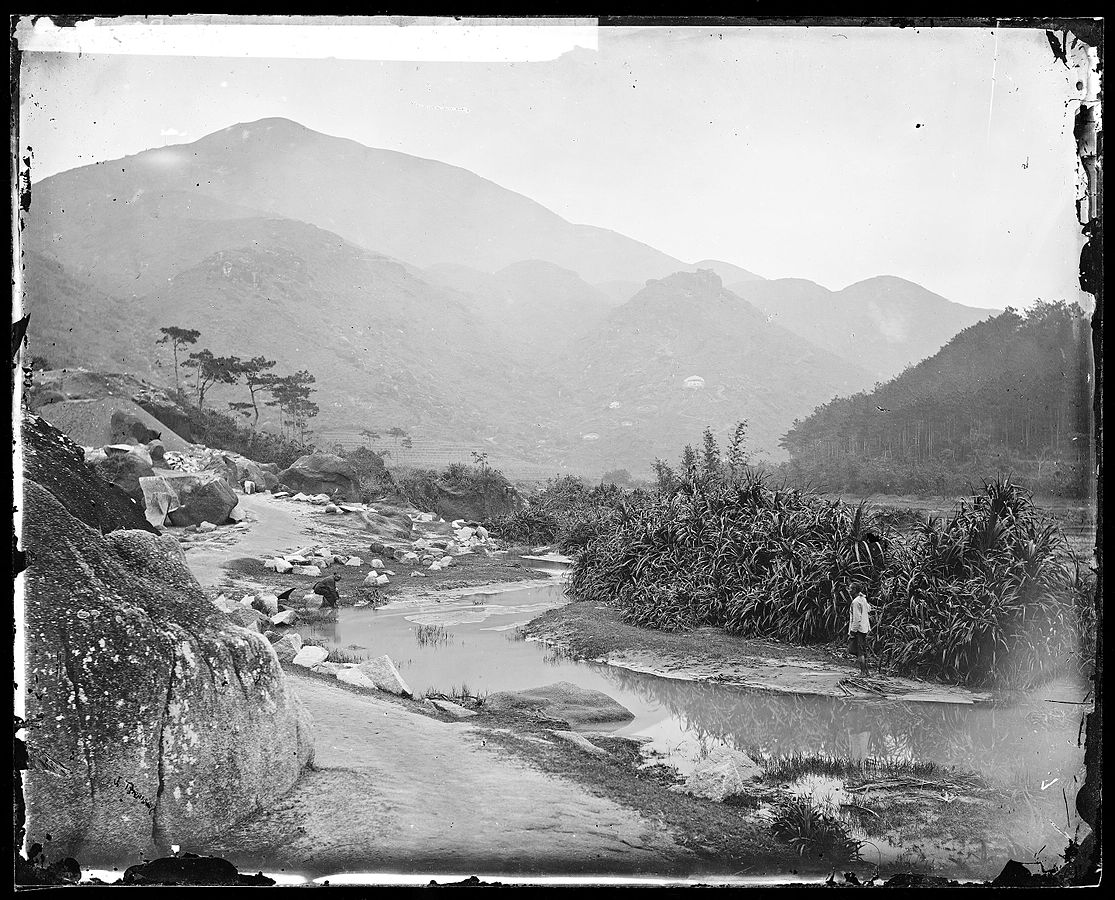

Pearl River, 1870

Pearl River, 1870Saving the Honor of the People of Gugangzhou

In 923, an agricultural tax collector called Gao Song arrived in Gugangzhou to collect 40,000 dan of grain for the state granaries in Nanxiong.34 Filling up the state granaries was regarded as a matter of priority for the government due to the regular occurrences of grain shortages and famine. However, in 923, the state of grain supplies in Gugangzhou was dire. As Tingfan was the government official responsible for building grain reserves in the area, he and Gao Song faced a predicament: the granaries were devised to keep the price of grain stable and to protect undeveloped regions from famine; but where were they to find grain from already starving citizens?

Zhang Tingfan and Gao Song knew well that famines and hunger had been the cause of many rebellions and uprisings throughout Chinese history. Even since the fall of the Tang, there had been repeated attacks in the countryside by groups of bandits the size of small armies; villages were pillaged and peasants suffered from hunger and poverty. The risk of rural rebellion was in the air.

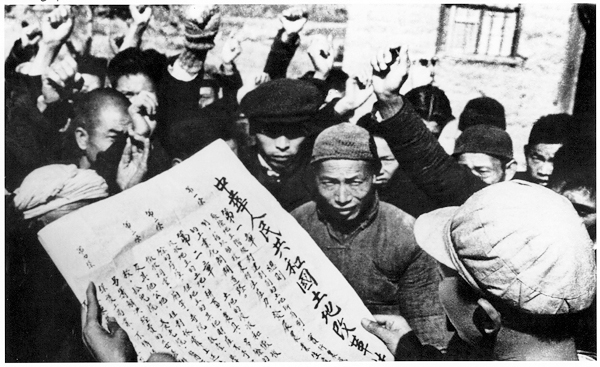

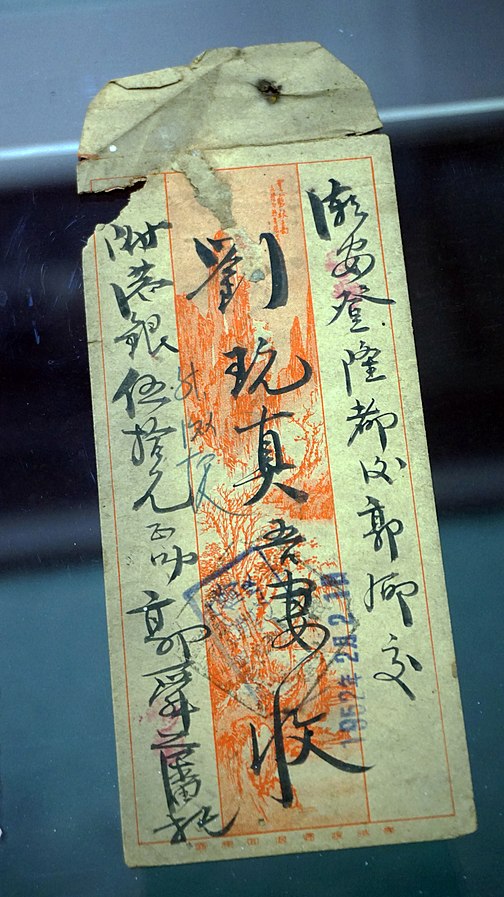

Tingfan decided to see what he could do to help the people of his area pay the tax. He sent his nephew Zhang Ku to their ancestral home in Gugangzhou to convince their relatives to donate some of their wealth to the cause. At the age of 46, Ku was married to the daughter of a county magistrate, and his youngest son, your great (x34) grandfather Zhang Chang, was a four year-old toddler. Ku discussed at length with his wider family, and they agreed to donate 360 liang or taels35 of gold from Ku’s grandmother’s dowry, 800 liang of silver, and 20,000 dan of grain from their own reserves to the national granary, out of pocket.36

The Imperial Government was grateful as Zhang Tingfan and Zhang Ku prevented a potential uprising. The people of Gugangzhou were grateful as a large debt with possible penalties was avoided, and they paid your ancestors back gradually. Tingfan and Ku each received 25 thousand dan of grain. The following year, Ku bought another 5000 dan of grain in reserves, which he split equally among his three sons.

Zhang Tingfan Dies

Some 14 years later, in 937, Tingfan died in Gugangzhou. Zhang Ku, himself at the ripe age of 60 at the time, mourned Tingfan like a father. Because his uncle did not have any biological children to inherit Tingfan’s assets, half of his considerable land went to Zhang Ku, and the other half to Tingfan’s successor at the Changpingsi (i.e. the local department in charge of grain reserves; the second half thus went to the government).

Three Sons of Zhang Ku: The Start of Three New Zhang Clan Branches

Zhang Ku died at the old age of 85 in 961 AD, leaving three sons and considerable riches.

The revenue derived from the land inherited by Zhang Ku from Tingfan, combined with the income from new land that Zhang Ku had purchased in Guangzhou, ensured the continued wealth and prominence of your Zhang family in Szeyap. Thanks to the family’s riches, and especially thanks to the military achievements of their great-uncle Yanze in fighting the Khitan Liaos, Zhang Ku’s three sons were all granted honorary titles. Moreover, all three branched out to start their own Zhang sub-clans.

The eldest son, Zhang Rong, obtained the honorary title of Chaolie Dafu,37 which means “Grand Master for Court Audiences.” In a clear sign of the close friendship between the Zhang family and the agricultural tax collector Gao Song, whom Tingfan and Zhang Ku had helped raise grain for Gugangzhou, Zhang Rong married the daughter of Gao Song. They remained at Hanwu Bridge, in Xinhui County. His descendants would later be known as the Xianlang Longshui branch of the Zhang Clan.

Zhang Ku’s second son, Zhang Hua, obtained the honorary title of Chaoyi Dafu,38 which means “Grand Master for Rites.” He married Ms. Lu, the daughter of a certain Lu Wanzhuang. They moved to Luwuqiao in Xinxing (also called Zhangqiao, which much later was merged into Kaiping County). His descendants became known as the Zhang Clan Zhangqiao branch.

The third son was your ancestor Zhang Chang.

936, Zhang Chang: Founder of the Zhang Clan Shagang Branch

Liangjinshan (orange), Shagang (yellow), Longgangli (red)

Liangjinshan (orange), Shagang (yellow), Longgangli (red)Zhang Chang was born in 919 A.D.39 In 936, at the age of 17, he left the safety of his home in Gugangzhou. Like his middle brother Zhang Hua, Zhang Chang settled in another area of Szeyap, in a place that is part of Kaiping today.

Today, your great (x34) grandfather ancestor is still credited with the development of the area he settled in, which was called Shagang (today’s Shagang Residential District, Kaiping, Guangdong). When he arrived at Liangjin Mountain from Hanwu Bridge in Xinhui, the area was quite a sorry sight:40

“...At the time, there were only forests and grasslands for tens of miles around. People were worried about wild beasts during the night. Besides Zhang Chang and his family, there were only five other families: the Xu’s, the Chen’s, the Li’s, the Mo’s and the Lei’s. They could not have been more than thirty or forty people in total.”41

Establishing Yongleli Village

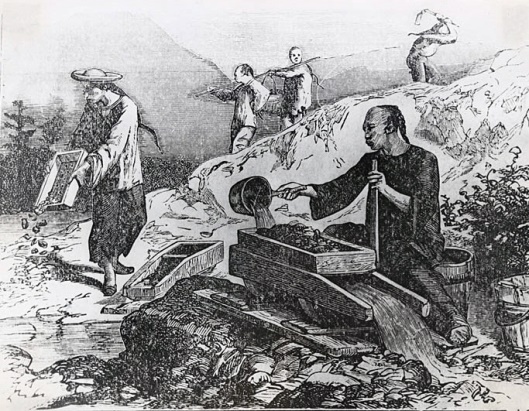

Peasants at work

Peasants at workZhang Chang did not waste any time. He settled on a plot of land 250 m away from the foot of Liangjin Mountain. He burnt down the forests, chasing out its beasts and poisonous snakes. He cleared up over a dozen hectares of land to grow rice and grazed sheep and cattle. He offered compensation to those that were willing to cultivate and plough the land. Before too long, the area turned into a bustling village. By the end of the year, the village had harvested several dan of grain. The village was named Yongleli.42

With the income made from selling their produce in Gangzhou (today’s Xinhui County) and Guangzhou, they bought basic household items, while the additional income was shared among their families.

Zhang Chang also set up a public welfare granary for surplus goods and produce, only to be called upon in extreme circumstances: when people fell ill and could no longer work or feed themselves, during famines, etc. In times of peace, he took it upon himself to educate the younger generations. As a result, many people of the surrounding areas moved to Shagang, with the population rising to over two thousand families.

After settling in Shagang, Zhang Chang married Ms. He, a daughter of He Bochuan, also from Yongleli. By the time his father died in 961, Zhang Chang was already 43 and a prominent government official himself. Largely due to the military achievements of his great-uncle Zhang Yanze, he obtained the honorary title Chaoqing Dafu,43 which means “adjunct grand master.”

Zhang Chang Dies, While A New Imperial Dynasty Is Born

The chaotic period of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms was eventually brought to a halt by a general named Zhao Kuangyin, or, as he became better known: Taizu, the first emperor of the Song Dynasty.

The Song Dynasty was a new dawn for China, with great advances in agriculture and industry. The civil service and imperial examinations came to dominate the lives of the elite, and the deterioration of central control that had taken place during the chaotic Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was translated into a revitalization of Confucianism and Imperial strength.

In 976, 16 years into the Song Dynasty, Zhang Chang passed away at the age of 57. At the time of his death, he had been leading the development of Shagang for forty years, transforming Shagang from a wilderness into the political and economic center of Yining County. With the county’s main market now located in Guzhou, Shagang,44 people in and around the area had nothing but respect for him, erecting a statue in his honor.

Shagang's Place in History

In 1982, a county-level archaeological survey team investigated the historical territory of Shagang. While the area of former Guzhou Village had turned into unremarkable village farmland, the local villagers were still able to tell stories from the collective memory about the “heyday” of Guzhou, when it was bustling with activity. Red bricks from the old city wall were found scattered around the area.

By the early Ming Dynasty, three new villages were thriving in the area. By the early Qing Dynasty, Shagang abounded in grain and garlic bulbs. A deep water wharf was constructed in Jinshan Village / 金山 村, opening the door to foreign trade. Shagang’s economy boomed as the famous roasted garlic from Jinshan was sold in America and Southeast Asia.

Though Shagang may not be your “closest” ancestral place, your great (x34) grandfather Zhang Chang pulled off a truly impressive feat by building a dynamic and prosperous region from the ground up.

Garlic bulbs

Garlic bulbs1506, Ming Dynasty: Zhang Shiquan Arrives in Longgangli

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Fast-forward 530 years to the heart of the Ming Dynasty. The Ming had started in 1368 and marked the return to a Han Chinese dynasty, following the foreign Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). It was a golden era for maritime expeditions, trade, and strict government control.

Zhang Shiquan: Humble Beginnings as a Duck Farmer in Longgangli

The year is 1506: the first year of Ming Dynasty Emperor Zhengde’s reign (1506–1521). The first person of your Zhang clan to arrive and settle in Longgang village was your great (x15) grandfather Zhang Shiquan.45 A native of Shagang, he and his brother Zhang Shitian, moved to Longgang in Chishui town. They settled on “Flying Goose Mountain” and ran a duck farm.46

During Shiquan’s life in the mid-Ming Dynasty, Guangdong experienced considerable economic and population growth. The production of silk and other textiles, sugar, and handicraft products greatly increased. Commercial activities accelerated as Guangzhou became the largest center of commerce in Guangdong and China's most important port for the international maritime trade. Guangdong merchants also transported the province's products to sell in other parts of China or abroad.

However, as the Han Chinese population in Guangdong increased, so did frictions with local, non-Han Chinese tribes. Around the time Shiquan moved to Longgang, imperial military campaigns to suppress tribal uprisings in Guangdong were not uncommon. Another form of increasing control was to restructure administrative jurisdictions and establish new counties with clear authority and reporting lines back to the Imperial Court. Two of today’s four Sze Yup counties – Enping and Taishan – were established around the period of Shiquan’s move (Kaiping was only established much later, in 1649).

Emperor Zhengde (1491-1521)

Often reputed to be reckless and foolish, known to indulge in women and neglect his duties, it was under his reign that China experienced first direct contact with Europeans, who started trading with Chinese merchants in southern China. Zhengde was fascinated by foreigners, and invited many Muslim envoys, advisors, and eunuchs at his court. Learn more.

The Legend of Zhang Shiquan: The Accidental Official

Fengshui master

Fengshui masterWe found several accounts relating how Zhang Shiquan supposedly went from duck farmer to official of the highest ranking.

According to an oral history interview conducted in 1987 with a local Zhang clan farmer in Wapiankeng, Zhang Shiquan was looking after his ducks on Mount Fei‘e when a fengshui master emerged from the woods, and asked him the way to Chikan. Seeing as it was already dark, Zhang Shiquan advised him to wait until the next day, offering him a bed and a hot meal in his humble abode.

That night, Zhang Shiquan killed a duck to welcome his guest. To thank him for his kindness, the fengshui master offered to advise him on the re-burying of any ancestors. At the time, the Zhang clan ancestors were buried in Shagang, about a day’s journey away. The fengshui master waited for Shiquan to collect his mother’s and his other ancestors’ bones, and when he returned, he laid them to rest atop Mount Fei’e beside the duck coop.

Early the next morning, as Shiquan was about to let his ducks out of their coop when he stepped on something hard and pointy that was lodged in the mud. He was astonished to find dozens of silver coins sticking out of the ground, so he hurriedly dug them out and brought them home. With his newfound wealth, Shiquan bought a large piece of land in Longgang.

The Prophecy

Up north, in the Ming capital of Beijing, Emperor Zhengde had just ascended the throne. He had heard of a prophecy that a new emperor would be born in a place called Jinji (literally “Golden Rooster”) in Kaiping. According to the prophecy, the new emperor’s birth would be announced by a pair of roosters crowing in Jinji.

Anxious about being overthrown so soon after coming to power, Zhengde sought the advice of a fengshui master. To prevent the prophecy from coming true, the master recommended building a trench leading to Jinji, and to bury a chain within it – symbolizing the enslavement of the roosters, and thus the annulment of the prophecy.

Zhengde sent an imperial envoy to complete this task. The envoy started from Qitou Mountain, and dug a trench that went across the five mountains of Shaomou, Wang, Wuzhi, Mojian, and Shichutou.47 However, when the imperial envoy’s project reached the borders of Chishui, the skies broke into a terrible rainstorm, and the armies’ provisions were ruined. The envoy saw that there was no way he could finish the project according to schedule, and felt extremely anxious.

Fengshui

Literally “wind-water” in English, fengshui is an ancient Chinese philosophical system focused on harmonizing people with their environments based on the observation of heavenly time and earthly space. The quality of fengshui was believed to have direct consequence on the quality of life, not just for an individual, but for the entire family or clan. Poor fengshui, for instance, could enrage the ancestral spirits and bring misfortune upon a family for generations to come.

Zhang Shiquan to the Rescue

He would have failed to complete his mission, if it hadn’t been for Zhang Shiquan, who provided his armies with three months’ worth of provisions.

To thank this benevolent man for his generosity, the emperor sent for Zhang Shiquan. However, upon receiving a summons to court, Zhang Shiquan believed that he had committed some sort of crime and that the emperor would punish him; at the same time, he knew that if he didn’t go, he would be killed all the same. His brother convinced him to obey the summons, and, resigned, he travelled to the capital.

Official

When Emperor Zhengde received him, he asked him what position he wished for in office. Shiquan replied he did not want to be an official, and that he wasn’t interested in money. The emperor still wanted to reward him somehow, so he asked him: “Every official corresponds to a certain rank in the Jiupin system. Which ranking do you desire?”

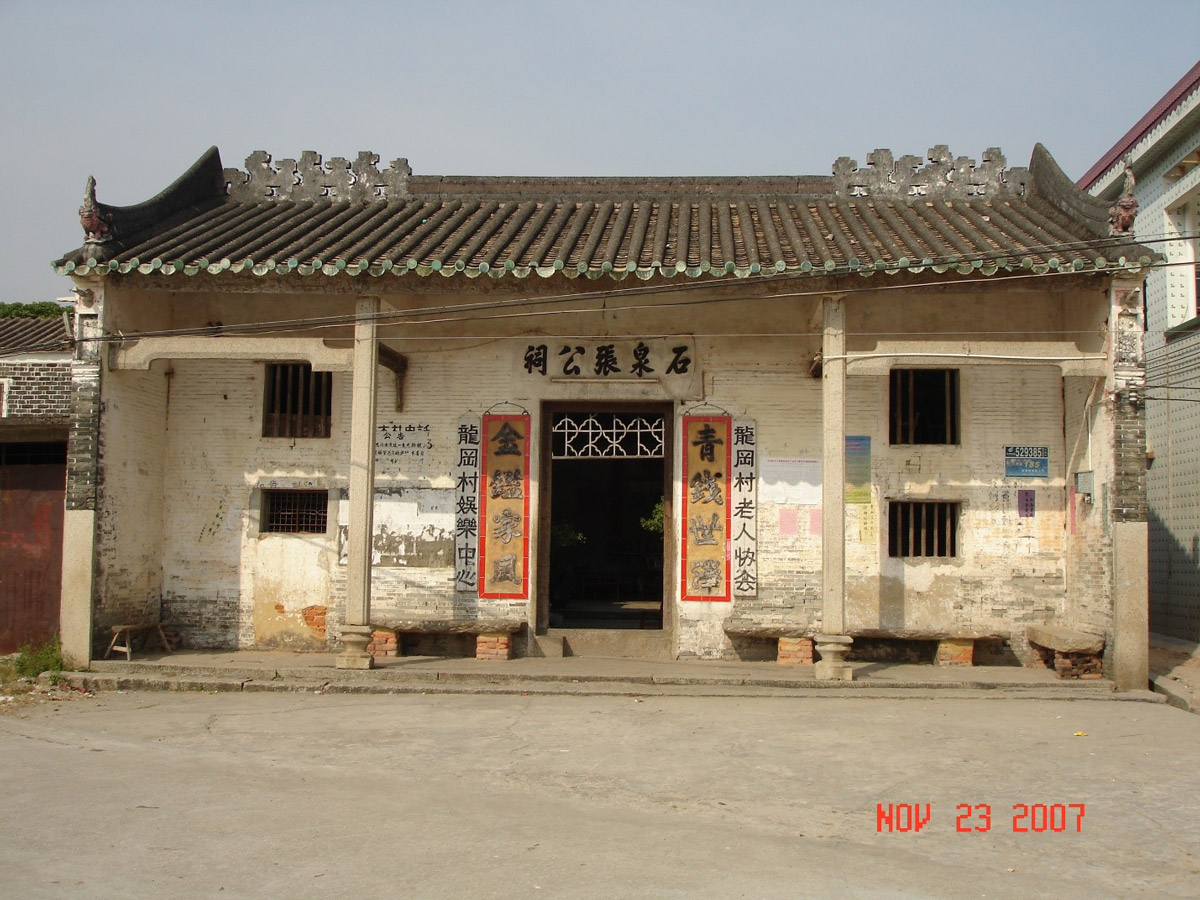

Shiquan did not know how the ranking system worked, and, mistakenly thinking it was the lowest, he “humbly” replied that he wished for the “first rank.” Thereupon, the emperor bestowed a set of first rank official robes upon him and his wife. Zhang thought the clothes were elegant, and so wore them on his journey home. Later, his descendants would paint a portrait of him and his wife cloaked in the robes, and built a temple in his honor. The large painting was then made to hang in the Zhang Shiquan ancestral temple for future generations to revere.

From Our Own Interviews in Longgangli...

When My China Roots visited Longgangli, our interviewees told a similar, though somewhat shorter story. In their version, Zhang Shiquan’s guest was not a fengshui master, but a government official. Moreover, they added that historically, every time an official envoy visited the village to collect grain taxes from farmers, no matter their rank, when they saw the painting of Zhang Shiquan in his official robes, they would bow down before his image. Not only that, but they would not dare enter the temple using the main entrance, and only used the side door to come and go.

Zhang Shiquan (right) and his wife

Zhang Shiquan (right) and his wife1644-1681: Ming-Qing Transition Turmoil Reaches Kaiping

Zhang Penglong: Delayed Implementation of Dynastic change

The tree where the last Ming emperor hung himself in today's Jingshan Park, Beijing

The tree where the last Ming emperor hung himself in today's Jingshan Park, BeijingFast forward yet another 100 years or so. The year is 1644; your great (x9) grandfather Zhang Penglong (born around 1640s) was possibly playing in the rice fields next to his home in Longgangli. In distant Beijing, the last Ming emperor hung himself from a tree next to the Forbidden City, capitulating to the invading peasant armies.

The Manchus, a tribal people from the north, seized this opportunity to move in and replace the Ming. In 1644, they proclaimed the start of the Qing Dynasty, with Beijing as its capital. It would take another forty years, however, for their conquest to be complete. Many Ming loyalists had fled to the south, garnering support for resisting the new foreign barbarian rulers.

In late 1646, a descendant of the founder of the fallen Ming Dynasty set up government in Guangzhou and crowned himself the Shaowu Emperor. Refusing to acknowledge the new Qing regime, he claimed to be the true ruler of all of Ming China. Interestingly and confusingly, that same month, in the same city, another Ming throne pretender proclaimed himself the Yongli Emperor. For two months, life in Guangdong was disrupted while the two pretenders fought each other, until the Qing army captured Guangzhou, killed Shaowu and sent Yongli fleeing across southern China.

Being a mere 120 km removed from Guangzhou, Zhang Penglong’s family will at the very least have heard about the Imperial turmoil, when they were visiting the local market town or talking to fellow villagers in the fields.

Kaiping Under the Qing

1649 saw the official establishment of Kaiping county. In 1650, the Manchu general Shang Kexi took over Guangdong, and Kaiping County officially fell under Qing territory in 1651. The Qing inherited the Ming’s defence station system, responsible for ensuring the county’s military security. In the county capital of Kaiping, these included a chief officer, 3 lieutenants, and 300 soldiers. A small camp was set up in Chishui, your Zhang ancestors’ own market town, with one lieutenant and 50 soldiers.

The freak weather gave locals no respite, for in the two years that followed, the area was hit by massive floods. The fields were submerged with water, attracting all sorts of pests and insects. In 1653, locals suffered a great famine, and unless Zhang Penglong’s father Zhang Tingshu had access to reserves, your ancestors will also have gone hungry, if not worse.

It did not take long however, before Ming and Yongli Emperor-loyalists in the region staged a revolt against the new Qing rulers. The revolt took place only 40km from Zhang Penglong’s house in Longgangli. In July of 1654, a general loyal to the Ming called Li Dingguo laid siege to the Xinxing County capital (today’s Xinxing County, Yunfu City). Later, Li ordered the invasion of the Kaiping county capital. In December, the Qing sent General Juma Bayara and an army of elite military forces to attack Li Dingguo’s forces, resulting in the return of Kaiping under Qing rule.48

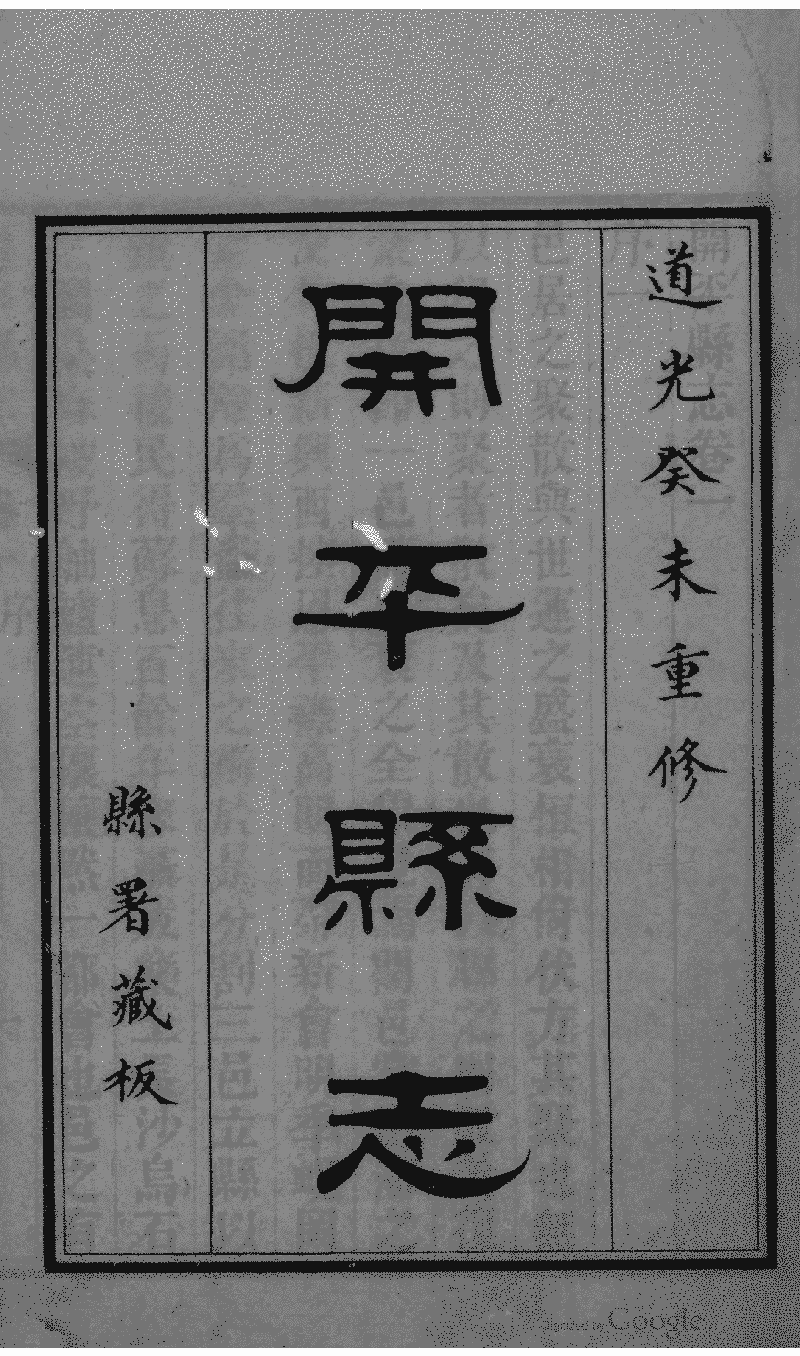

The Kaiping County Gazetteer

The Kaiping County Gazetteer

The Kaiping County GazetteerOne of the important historical sources for this report was the Kaiping County Gazetteer.

Local gazetteers in China are encyclopedias of specific places, drawn up by government and containing wide-ranging information on geographic, administrative, economic, and cultural features and changes. They typically also contain information about specific government officials, dignitaries, prominent clans and other issues of relevance for the area.

The Kaiping County Gazetteer started being maintained when Kaiping county was established in 1649. Your great (9) grandfather Zhang Penglong was growing up, and the Manchu armies of the fresh new, foreign Qing Dynasty were still fighting with southern Ming-loyalists.

Between 1649 and 1993 (when the administrative status of Kaiping was changed to a county-level city), the Gazetteer was updated nine times: seven times before, and twice after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The updates in 1823 and 1932 were the most comprehensive. The 2002 update was undertaken by the local government’s Office of the Kaiping Gazetteer.

1662: Kangxi’s Great Clearance

Kangxi Emperor

Kangxi EmperorIn 1662, the Qing Emperor Kangxi released an edict that would not only impact life in Kaiping for the next two decades, but would have an impact that would return to wreak havoc in the wider region two centuries later.

Following the final defeat of the Ming on the mainland, remnants of the Ming army led by Koxinga or Zheng Chenggong left for Taiwan and continued to attack the Mainland coast, while also trading with coastal residents. To break economic ties between them and the coastal mainlanders, Qing Emperor Kangxi ordered a major evacuation of the area. Along the coast, people were forced to leave their land and homes, and move at least 25 km land inward. Kangxi’s coastal clearance policy caused a major disruption to the economic and social life of China’s coast, and Guangdong was particularly affected.

Located around 40 km from the sea, Longgangli may not have been directly subjected to the evacuation order.49 Nevertheless, Zhang Tingshu and Zhang Penglong and their families would have seen caravans of distressed peasants and gentry alike, bringing their possessions and livestock to safety beyond the 25 km line.

1669: Lifting of the Clearance Order and Repopulating the Coast

In 1669, around the time Zhang Penglong’s son Zhang Yexu was born, the Kangxi Emperor officially lifted his evacuation order and started incentivizing both former coastal residents to return and new residents to move to the coast by giving them tax exemptions and free resources.

The process of re-populating the coast went slow, and by the time Yexu would have been a teenager, local counties were still calling for peasants to settle back on the coast.

With time however, the beneficial re-population policies were to draw hundreds of thousands of newcomers, especially Hakka. The frictions that would ensue between the returning indigenous population (“punti”) and the newly arriving Hakka people were to come to a bloody head some 180 years later. Little did Yexu know that that future conflict, known as the Hakka-Punti Clan Wars, was to be among the reasons why his great-great-great-great grandson Bein Yiu Chung would move overseas.

1662-1669: Freak Weather

As if the forced migration and re-population due to Kangxi’s Great Clearance Order did not pose enough hardship, extreme weather conditions made the homecoming even more brutal, with storms, hurricanes and hailstones “the size of bricks.”50 In fact, for almost every year between 1662 and 1669, Kaiping had been suffering earthquakes, droughts, pest infestations, famine, and as many as five typhoons in 1668 alone.

Natural Disasters in Kaiping that Impacted Longgangli, 1680-1804 (from the Kaiping Gazetteer)

| Year | Disaster |

|---|---|

| 1680 | August: Great drought |

| 1687 | April: Heavy rain |

| 1689 | March: Drought |

| 1690 | February–May: Heavy rain |

| 1691 | March–May: Drought, price of rice surges significantly |

| 1696 | April: Drought |

| 1702 | June: Hurricane |

| 1703 | June: Locust plague |

| 1706 | May: Heavy rain, nonstop for 6 days and nights |

| 1724 | Earthquake in Kaiping, which can be heard from afar |

| 1750 | August: Hurricane and storm |

| 1752 | September: Hurricane and storm, residential houses damaged |

| 1777 | Autumn: Drought |

| 1786 | Autumn: Drought |

| 1787 | Summer–Autumn: Drought |

| 1791 | April: Heavy rain, residential houses damaged |

| 1794 | February–April: Drought |

| 1804 | April: Heavy thunderstorms |

1673: Wu Sangui’s Troops Plunder Kaiping

Wu Sangui

Wu SanguiIf by 1673, 29 years after having proclaimed their Qing Dynasty, the Manchu rulers thought they were solidly in their imperial saddles across the Empire, they were sadly mistaken.

Wu Sangui was a former Ming general, who had defected to the Manchus and helped the Qing quash Li Zicheng’s 1644 peasant rebellion and then lay siege to Beijing. In 1673, Wu started his own anti-Qing rebellion.

In 1676, his subordinate officer, Ma Xiong, entered Kaiping and his troops pillaged and looted wherever they went. Your ancestors Zhang Tingshu, Zhang Penglong and little Zhang Yexu will likely have lived in fear, and may even had to run or hide to avoid the marauding rebels. Fortunately, the troops eventually moved on from Kaiping, and Wu Sangui’s rebellion was quashed in 1681.

1757-1793: Setting the Scene for “The Zhang Clan Odyssey"

1757: Births of Zhang Huangpan and the Canton System

Around the time that your Zhang ancestors in Longgangli were celebrating the birth of your great (x5) grandfather Zhang Huangpan, some 2000 km to the north at the Imperial Court in Beijing, the Qianlong Emperor was making a decision that would somehow impact the lives of all Huangpan’s future descendants. In fact, the imperial decision was to impact China’s general relations with the outside world, up to the moment of writing this report.

In 1757, Emperor Qianlong started the “Canton System.” The aim of the policy was to limit foreign influence in China by tightly controlling China’s foreign trade, and so the Emperor ordered the closing of all of China’s harbors, leaving only the port of Guangzhou to allow for imports and exports.

Port of Canton (Guangzhou), ca. 1850, featuring traditional Chinese junk ships and steamliners. Wikimedia Commons.

Port of Canton (Guangzhou), ca. 1850, featuring traditional Chinese junk ships and steamliners. Wikimedia Commons.For China, the result was that it further increased its isolation from the outside world at a time when industrialising European powers were developing at breakneck pace. China’s overall restrictive attitude to trade furthermore greatly contributed to the disastrous and uncontrollable smuggling of opium.

For Guangzhou, the result was that it became China’s official door to the outside world, triggering its development as a coastal metropolis, some 100 km to the northeast of Zhang Huangpan’s home in Longgangli. Portuguese, English, Dutch, French, and Americans, all focused on Guangzhou in seeking a share of the lucrative trade in silk, tea, porcelain, and very importantly, as time went by, opium.

1793: Qianlong and Macartney

However, even for the trade passing through Guangzhou there were considerable limitations: trade was only permitted between October and March, and only a handful of formally licensed Chinese merchants were allowed to conduct foreign trade. Foreign traders were not allowed to communicate directly with Qing officials, yet foreign merchants were required to pay an annual tribute of 55,000 taels (roughly 75,000 USD) to the imperial court. In fact, the court was so intent on keeping the “barbaric” foreigners out of China that it forbade foreigners to study Chinese or read Chinese books at the Guangzhou port.

In 1793, when Huangpan’s son, your great (x4) grandfather Zhang Huadai, was around 10 years old, the British King George III sent Lord Macartney on a mission to China with the aim to convince the Qianlong Emperor to remove all of China’s trade limitations. Lord Macartney arrived on an impressive warship with a large entourage and 600 gift packages that required 90 wagons, 40 barrows, 200 horses, and 3000 porters to carry.

'No’

Unfortunately for the British delegation, the Qianlong Emperor reigned over perhaps the richest, most luxurious courts in all of Chinese history. Its splendor and magnificence made the British presents pale in comparison. As Lord Macartney offered the emperor his cases filled with telescopes, clocks, and watches, the Qianlong Emperor noted simply that China already possessed “everything” and that the British Empire could not possibly offer anything that he would need, let alone make him reconsider his aversion to international trade.

Lord Macartney is shunned by Emperor Qianlong, ca. 1792. Wikimedia Commons.

Lord Macartney is shunned by Emperor Qianlong, ca. 1792. Wikimedia Commons.Lord Macartney left Beijing and remained in Guangzhou before returning to Britain just a few weeks before Chinese New Year, failing to obtain any concessions from China.

The mission will not have had any immediate impact on Zhang Huadai and Huangpan’s lives in Kaiping beyond them perhaps hearing that an impressive and exotic fleet of ships were docked in the port of Canton (today’s Guangzhou). There was likely gossip and speculation in and around Longgangli about the delegation, who they were, and what their intentions were in the area.

Long Term Impact

Little did Zhang Huangpan know, the trend that Lord Macartney’s visit represented would have a deep and direct impact on the lives of his son Huadai and his future grandson, your great-great-great-grandfather Cheun Saan Jeung.

Decades later, the British would return, stronger and richer, to a China that had stagnated. This time, the British would get what they wanted. And this time they would leave the 90 wagons of presents at home and instead introduce a “Century of Humiliation” to China, a century filled with unequal trade treaties, foreign intrusion, forced opening of ports, and an opium trade that spiralled out of control.

Early 1800s: Cheun Saan Jeung’s Childhood in Longgangli

A Time of Population Growth and Agricultural Productivity

Cheun Saan Jeung was born in 1814 in Longgangli. In 1815, he would have been just a toddler when a big earthquake hit Kaiping, and could be heard from everywhere in Chishui.51

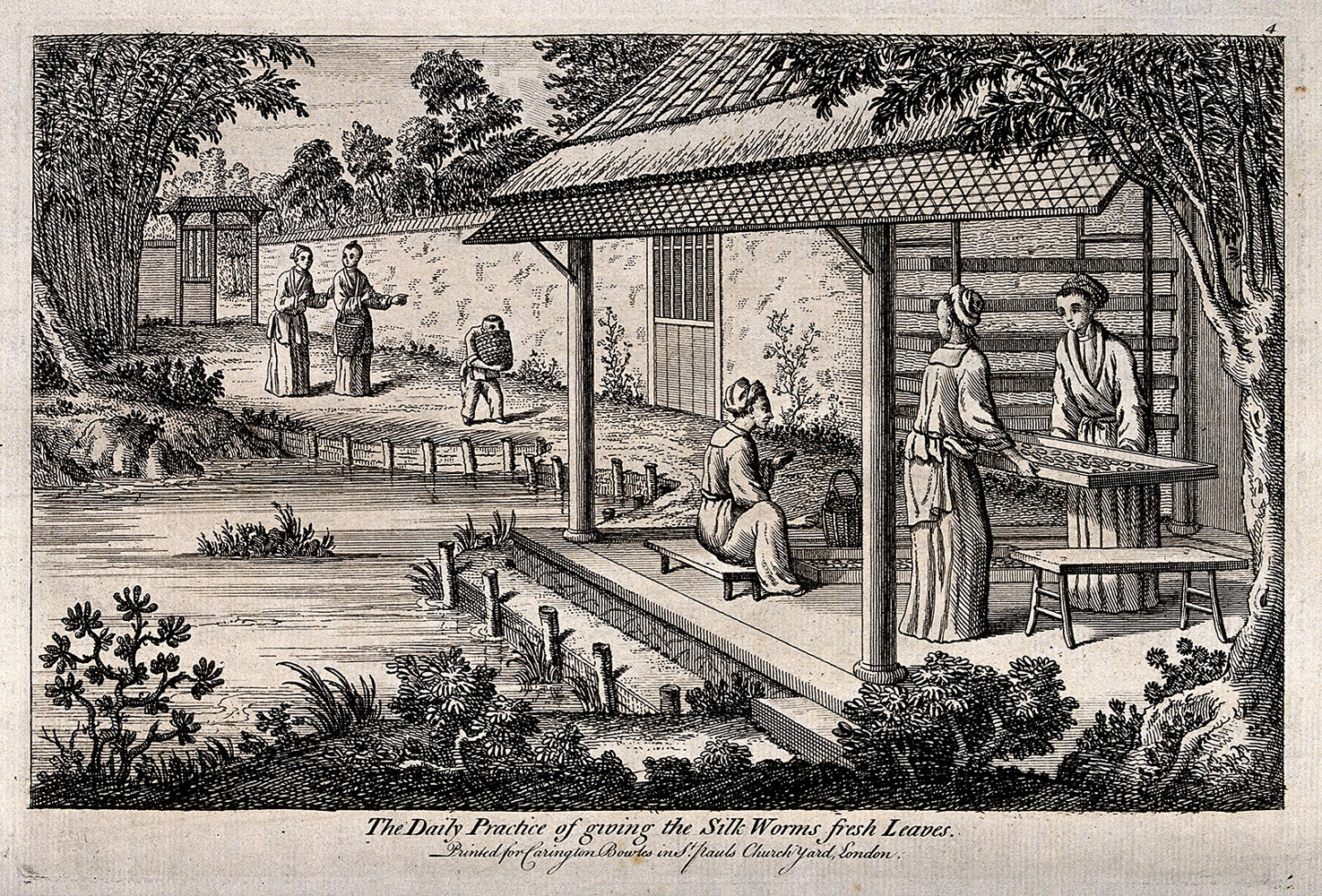

‘The Daily Practice of giving the Silk Worms fresh leaves.’

‘The Daily Practice of giving the Silk Worms fresh leaves.’Agricultural productivity in Guangdong had increased considerably over the previous decades. Wild longan trees had been felled to make way for mulberry trees and fish ponds, and the raising of silkworms had become a widespread endeavour. Food output had increased in part because maize and sweet potatoes (originally imported from the Americas) were now permitting dry hills and mountains to be tilled.

The population growth that Guangdong experienced during the Mid-Ming Dynasty times of Zhang Shiquan had continued to grow at an even faster pace. Innovation in Chinese agriculture, not just in Kaiping and Taishan but in China overall, had led to stunning population increase across the empire: from 100 million around the time of Zhang Penglong’s birth and Kaiping’s establishment around the 1640s, to 300 million around 1805.52

However, everything is relative, including advancement and growth. Notwithstanding Guangdong’s agricultural innovations and population growth, some 10,000 km to the west, Europe had been going through its “Age of Enlightenment” and had literally moved full steam ahead with its Industrial Revolution. The ensuing imbalances in technological and industrial advancement between Europe and China would soon disrupt the peaceful and simple countryside life of Cheun Saan Jeung and his only, newborn son Bein Yiu Chung, born in 1840.

19th Century (1st Half): Opium

Harvesting Seeds of Doom

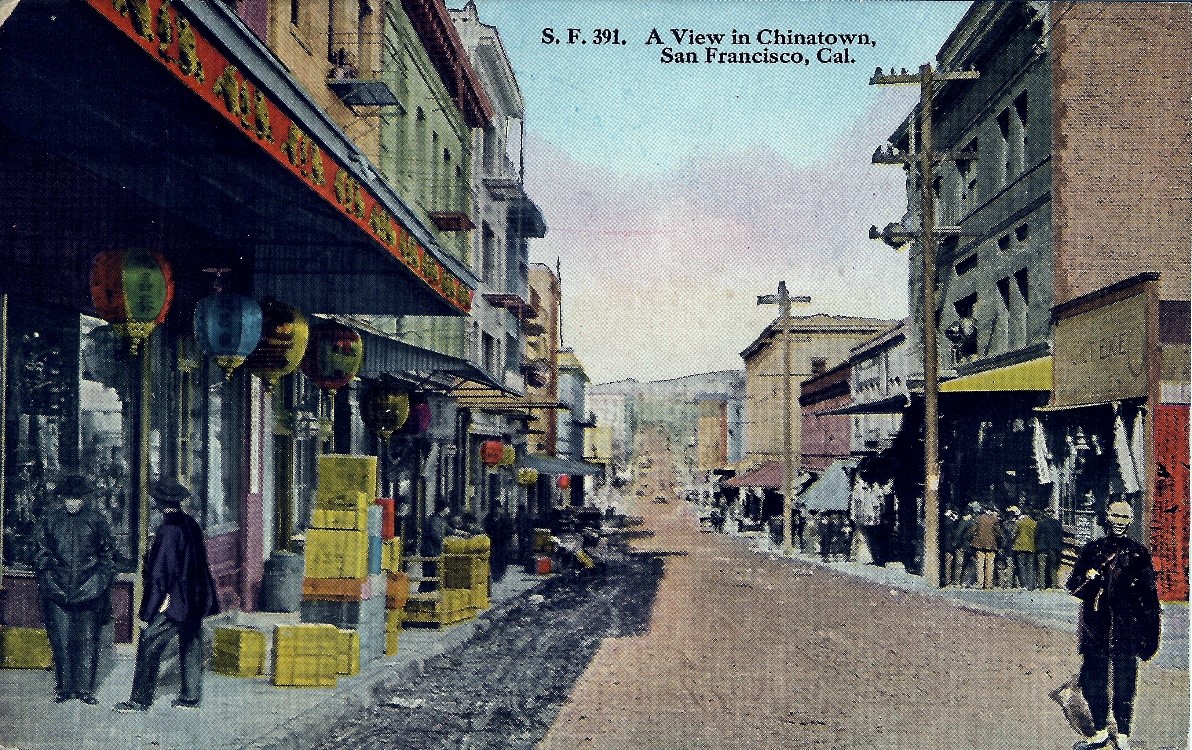

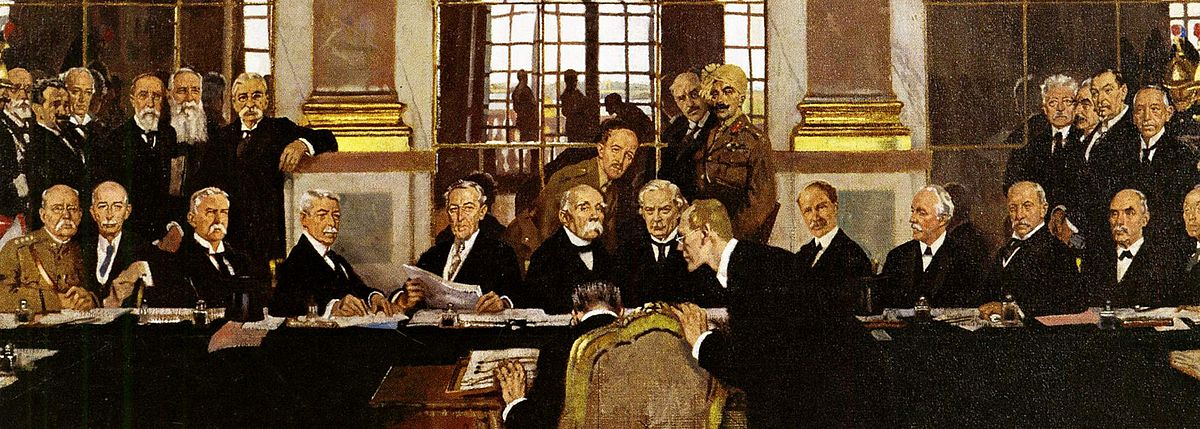

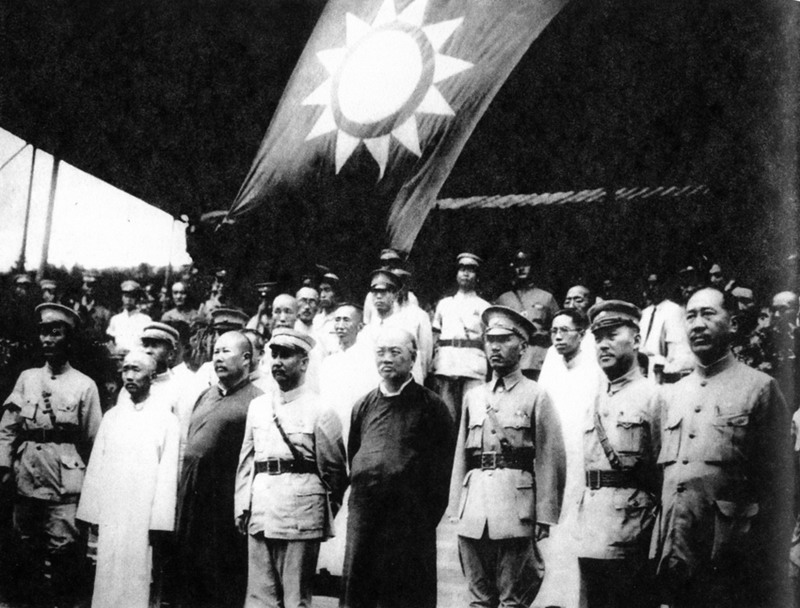

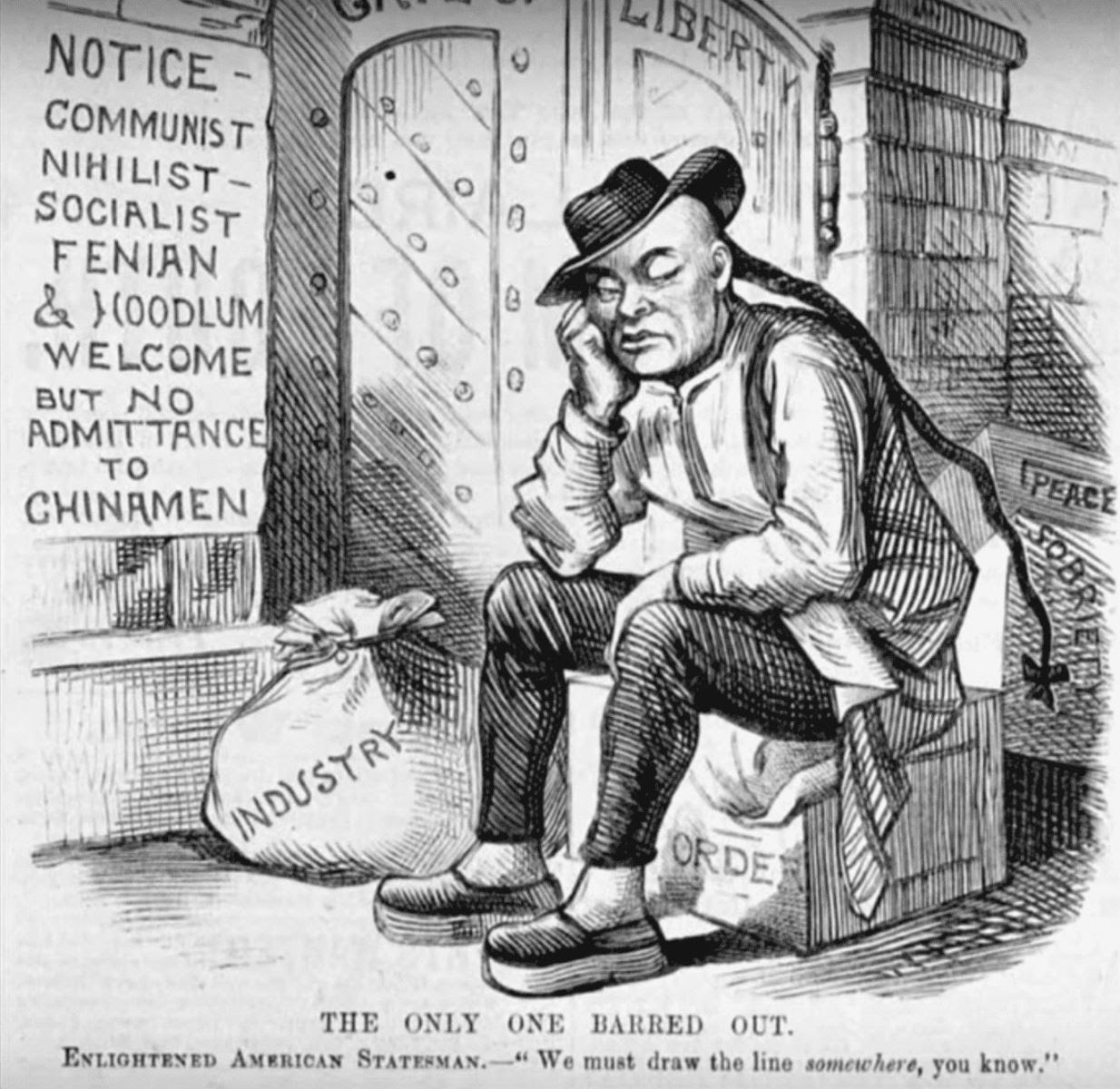

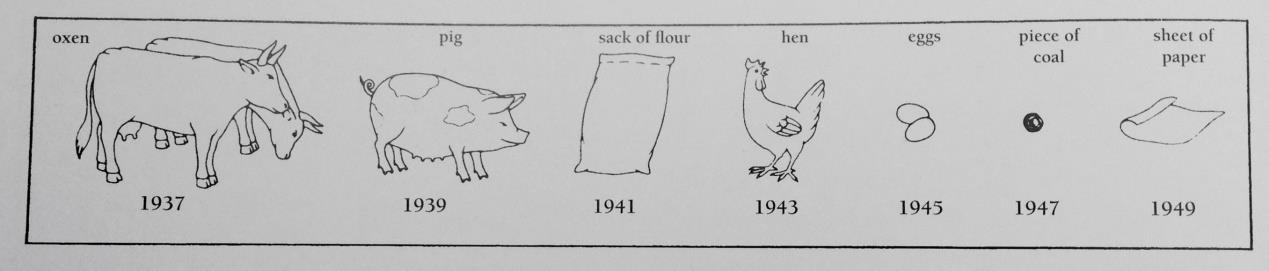

The period between the births of your great-great-grandfather Bein Yiu Chung and yourself is generally referred to as China’s “Century of Humiliation.” Starting with the Nanjing Treaty of 1842 and ending with the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, China found itself continuously humiliated and brought to its knees by foreign powers politically, economically, and militarily. It is not a coincidence that five consecutive generations – up to your father – kept leaving China to pursue better economic opportunities abroad during this exact period, only to occasionally return for largely family-related reasons.

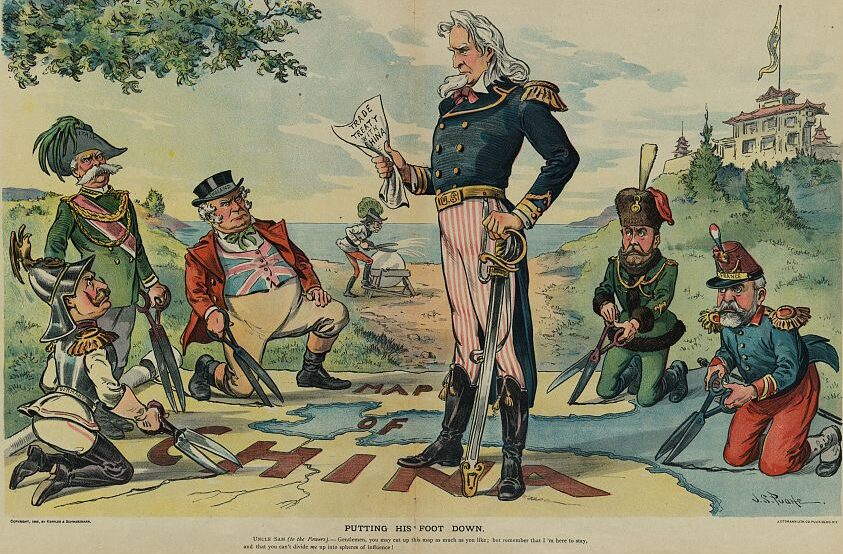

Uncle Sam ‘putting his foot down’, 1899.

Uncle Sam ‘putting his foot down’, 1899.Tea for the British, Opium for the Chinese

Since the early days of the Qing Dynasty in the second half of the 17th century, western and especially British demand for Chinese tea had been increasing sharply. By the 18th century, Britain was drinking so much tea from China that it had built up an enormous trade deficit. Eager to reduce the deficit, Britain tried to import tea from India and export European clothes to China. However, none of these experiments worked: The Chinese had little interest in Western goods and only accepted silver in payment. As a result, the British trade deficit kept growing.

Searching for ways to remedy the trade imbalance, the British finally found a product that interested the Chinese: Opium. The opium was grown by the British East India Company on its plantations in India, and transported by way of Southeast Asia with the help of overseas Chinese traders there. The growth and cheap production of opium on these plantations would be the start of China’s demise a century later.

Plant exchange with disastrous impact: Tea (above) for opium (below)

Plant exchange with disastrous impact: Tea (above) for opium (below)

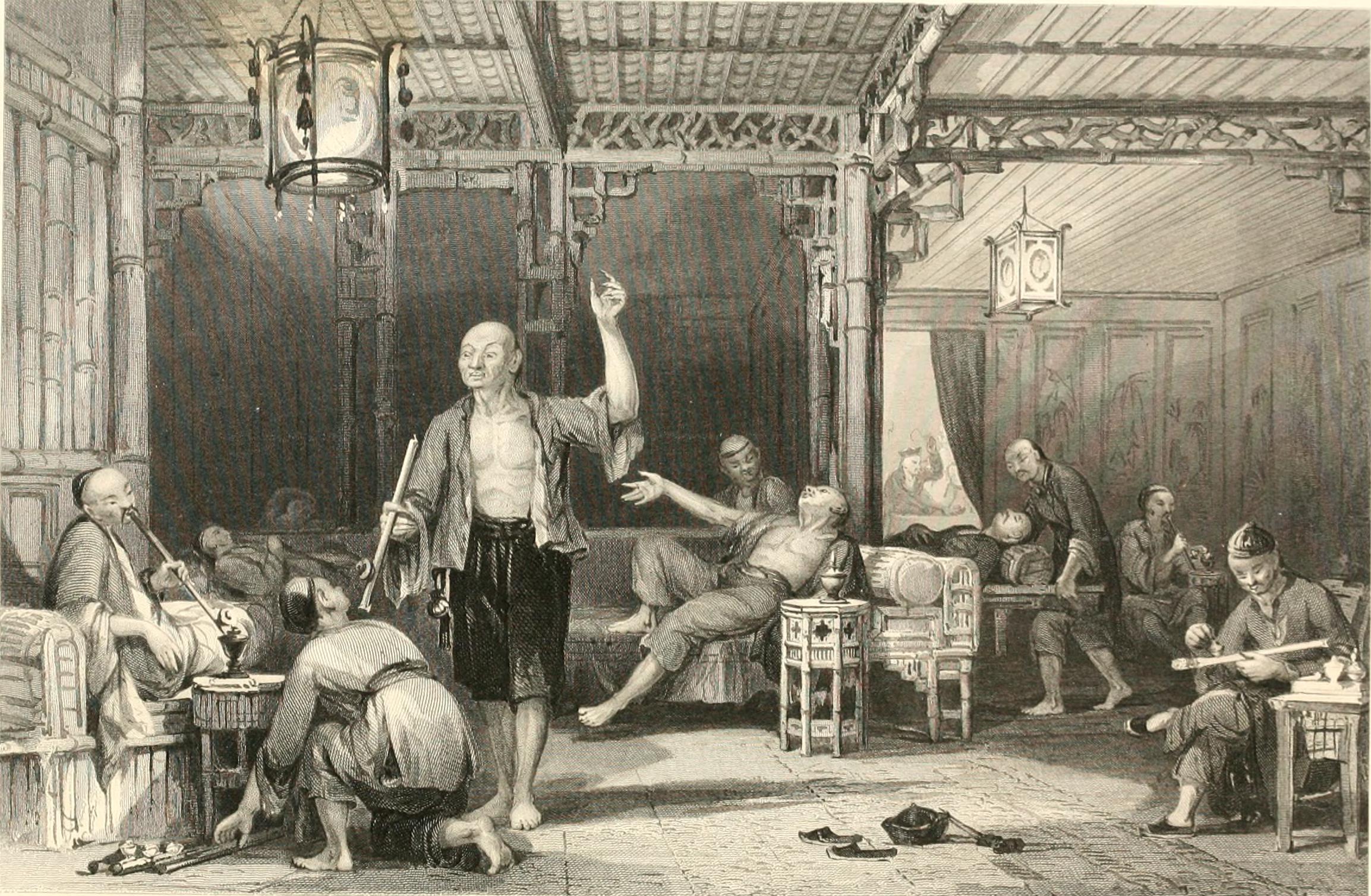

Opium

Opium came in different grades marketed for specific social groups. Opium from Malwa, India was the opium of the masses, while Bengali opium was higher quality and reserved for the wealthy. Opium produced in China’s Yunnan province was separated into four different varieties before it hit the markets, and the best of all domestic opium was custom-made for the Guangdong market. Opium imports and addiction across China throughout the 19th century was unprecedented and never again matched in world history.

1820-1837: Opium Runs Wild

The British East India Company started bringing their opium sales in cargoes to islands off the Guangdong coast where Chinese traders with fast and well-armed boats distributed the goods inland. Traders paid for the opium with silver, which the British could then use to buy more Chinese goods, especially tea. Often, tea leaves could also directly be traded for opium by small scale traders and smugglers. The impact on Chinese society was nothing short of disastrous. Due to Kaiping’s proximity to the coast, your ancestors’ environments were exposed to opium at an early stage.

Between 1820 and 1835, when Cheun Saan would have been a young man, China’s population of opium addicts increased a staggering 50-fold. To make things worse, in 1834, free trade reformers ended the East India Company’s monopoly on opium, which allowed private entrepreneurs from America to join the trade. Competition between and among British and American merchants drove down the price of opium further, which in turn increased sales and made the trade flourish all the more.

Cheun Saan watched the First Opium War unfold right in his backyard. Imagine what it must have been like: the society of his ancestral home was disintegrating due to drug addiction and there will likely have been a constant fear that the British Army could descend on Kaiping at any moment.

Chinese opium den, ca. 1858. Wikimedia Commons.

Chinese opium den, ca. 1858. Wikimedia Commons.A Prelude called Lin Zexu

By 1839, the overwhelming majority of men of Cheun Saan’s age – late 30s, early 40s – were smoking the drug, especially in Guangdong. Opium dens were everywhere, filled with pale, thin addicts smoking their opium pipes; some euphoric, some sleepy, others sick. Low-priced opium was easily accessible to farmers, and even some villages that did not have shops selling rice were tragically still able to sell opium.

At the Imperial Court in Beijing, Emperor Daoguang had had enough of the opium madness. In 1839, he appointed scholar-official Lin Zexu to abolish the trade. He sent Lin to Guangdong to the provincial government offices in Guangzhou. Lin arrested thousands of opium dealers and confiscated their opium without compensation.

Lin Zexu seizes opium, ca. 1839. Wikimedia Commons.