Editor’s Note: Names have been changed to respect the family’s privacy.

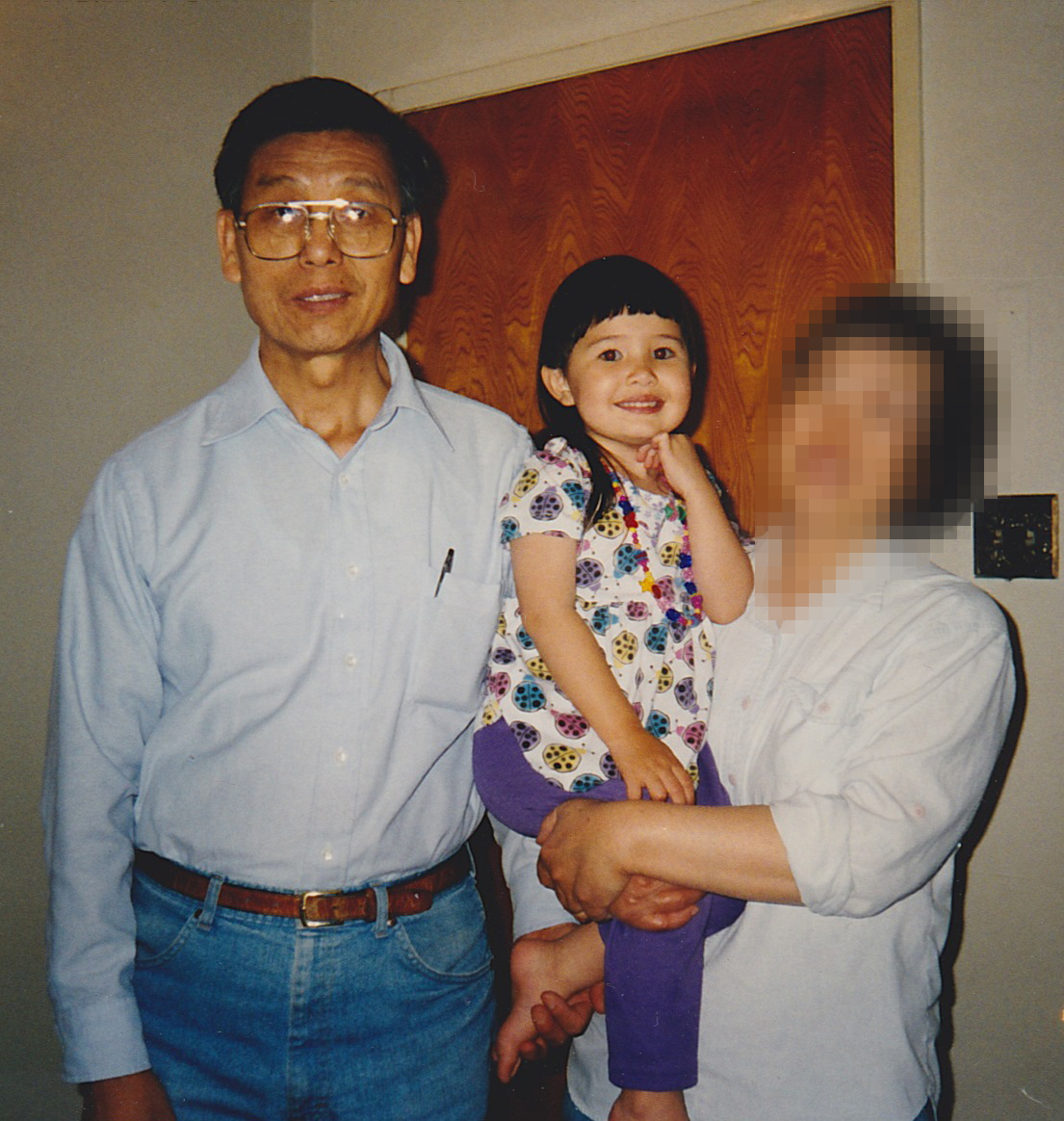

Erin Ross is the apple of her grandfather’s eye.

“My family says he was quiet and stoic, but he was always very warm to me,” she recalls. “Of all the grandkids, I was the only one to ask, ‘Grandpa, can you give me my Chinese name?’”

Chen Yiwei would give his beloved granddaughter an auspicious name with double meaning, Si Zhong 思中: in mid-thought, missing China. After all, he had journeyed far from home via Rio de Janeiro to southern California, where Erin’s Chinese-Brazilian upbringing often drew curiosity. “Why? Why do you look the way you do? Why does your mother speak so many languages? Why…?”

For Erin, the answers lie in the steppingstones of her grandfather’s story. “He was a trailblazer in every way,” she says with pride.

By the age of 12, Yiwei was the most educated person in town. Despite being the youngest son, he attended boarding school when most villagers in Hunan could not. This all changed one fateful day, when Nationalist-Communist infighting blocked his path home from school. Losing all contact with his family at age 14, he eventually followed a neighbor and emigrated to Taiwan.

Resuming his education, Yiwei became the first in his family to graduate from university with an English degree. When a friend recruited him to teach in Brazil, he took the leap overseas. Before long, he learned Portuguese, opened a neon sign business, and started his own family. After the military coups of the 1970’s and the economic instability of the 1980’s, they joined a wave of Brazilian immigration to the U.S., where Erin was born in California.

“He was very strong to handle all of that,” Erin muses. “And smart! He spoke four languages and married an educated girl from a higher social class. My grandma comes from a family of doctors and high political figures. My grandpa comes from very little. He had to be super open-minded.”

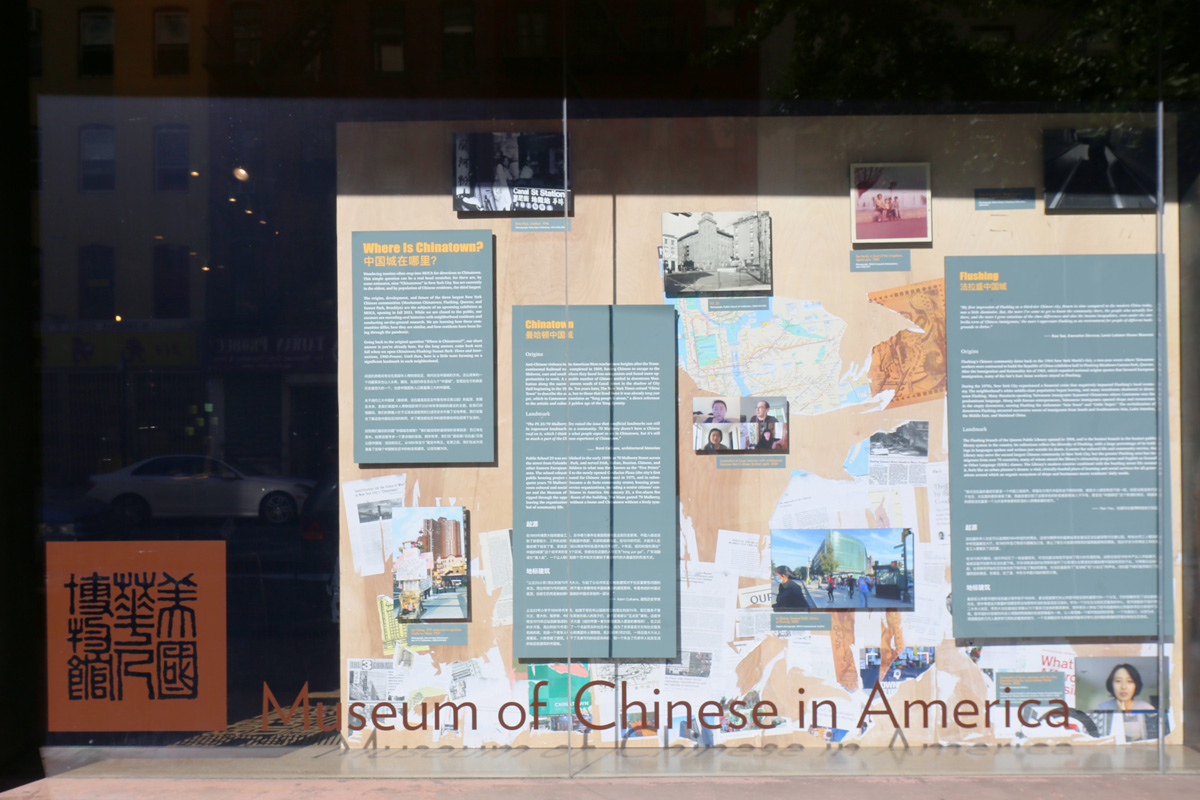

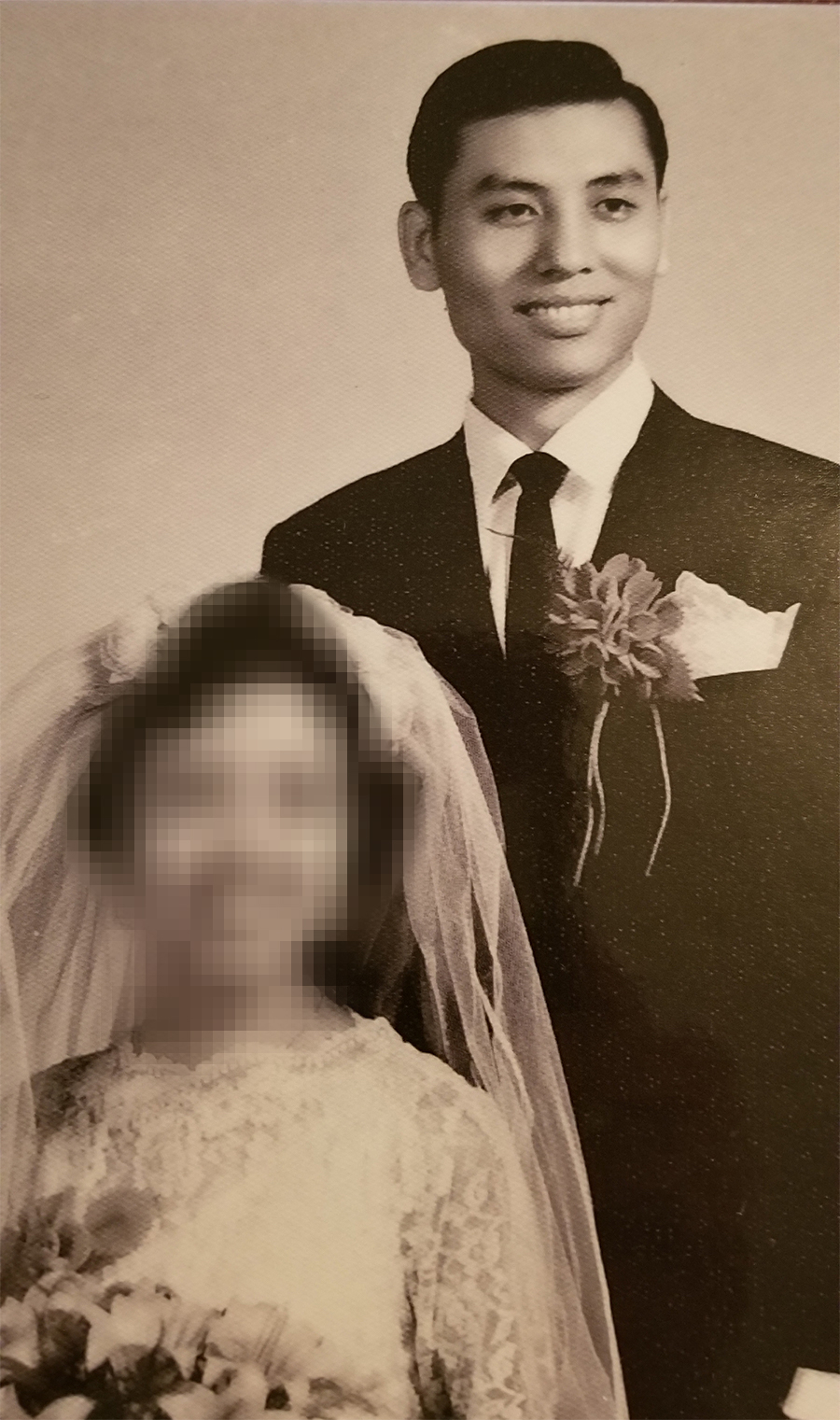

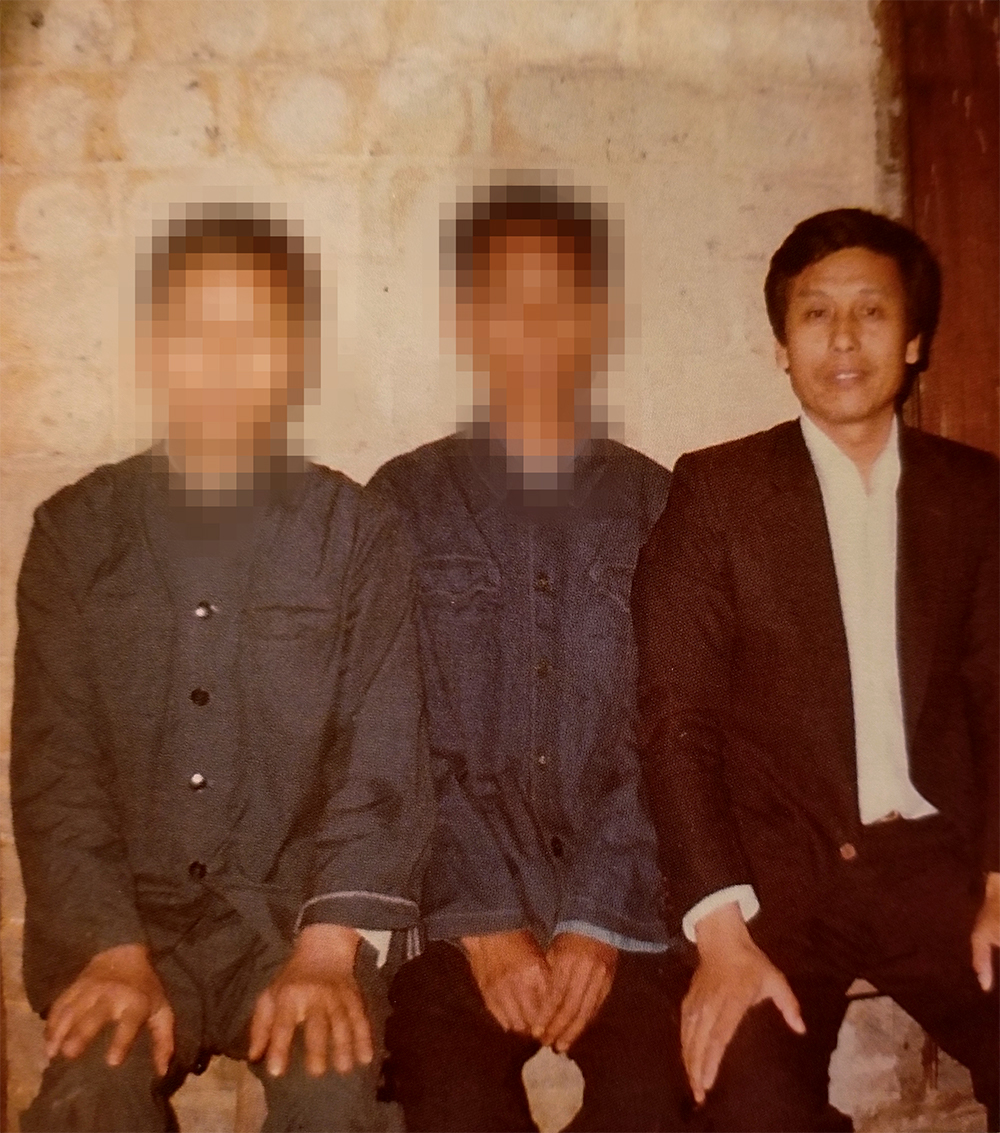

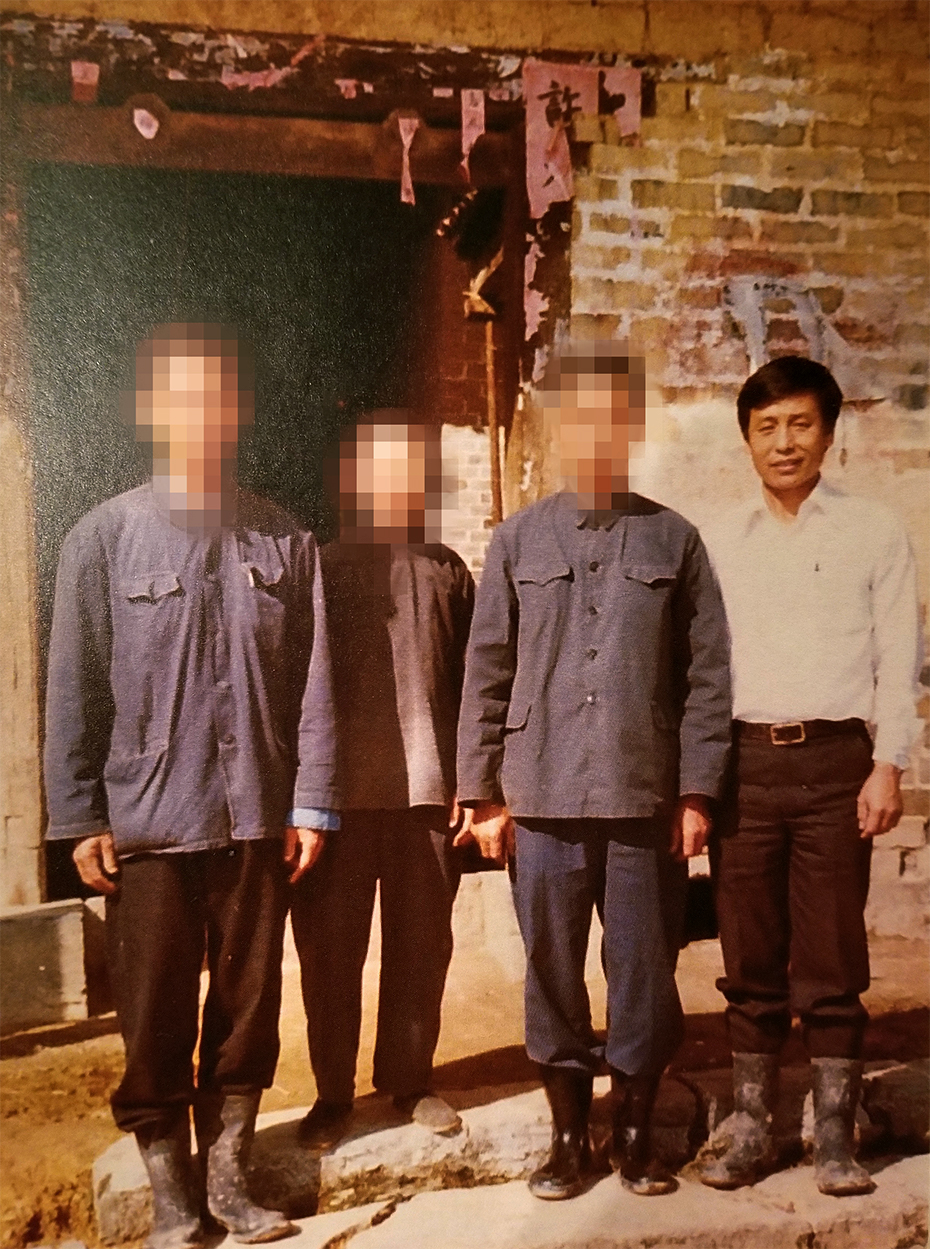

Erin treasures three photos of her grandfather’s life before the United States: one wedding portrait and two snapshots with his brothers from 1981 or 1982. Somehow, after more than 35 years, he found a way to re-establish lost contact with his family in China. As Erin’s Chinese name alludes, no matter how far he wandered, his longing to return home never left his mind.

“I always dreamed of going back to his hometown with him,” she shares. “When he died, my dream was gone too.” Needing time to grieve, she threw herself into her Master’s degree in engineering. After graduation, she felt ready to dream again. “I got sick of waiting and thinking I’ll do it later. I’m just going to do it!”

Now if her grandfather could find his family without the Internet, couldn’t she find them with it? Determined, Erin drafted a social media post, hoping to share his story online. As Facebook is blocked in China, she recruited friends to post it on WeChat on her behalf.

However, since WeChat posts are only visible to immediate friends, she still had slim chances of reaching one family out of millions. To make her dream a reality, Erin had to get local. “That’s when I knew I had to find a company. I googled, and My China Roots came up. Oh, you do this!”

Clues in hand, MCR researcher Liu Jingwen lost no time contacting all possible bridges with Yiwei’s community. She rang every organizational level of the local federation for returned Overseas Chinese, from the Hunan province office to the Hengyang city office. For one month, her calls went unanswered, until she finally got the personal number of a staff person at the county office. As it turns out, the official lines were cut since the federation hadn’t paid their phone bills!

With the county staff now onboard, the stage was set to circulate Yiwei’s story. At 10 am, his photos were posted in a WeChat group for local village leaders. By 12 pm – just two hours later – his family had been found.

“When we got the news, my mom couldn’t believe it,” Erin laughs. “Fifteen more cousins? This must be a dream!”

It was otherworldly for him to return. His whole family had thought he was dead.

The revelation was a shock for their family in China too. For years, they had also been searching for their kin. Hopeful, they asked the U.S. embassy to trace an old address for Yiwei’s first residence in California. When they learned about his passing, they feared it was a lost cause. Now, the WeChat post gave them a surge of hope. They had the exact same photos as Erin – and more.

“They had records I had no idea about,” she marvels. “A zupu [family tree book] that my mother’s cousin wrote up… and the letters and photos my grandfather brought back by hand. I could recognize his handwriting.” Finally, she learned the full story behind his family photos.

In 1981, Yiwei had boarded a flight from Brazil to Hong Kong. There, a relative met and guided him back to his hometown. He traveled light, only carrying mementos to bridge his transpacific family.

“It was otherworldly for him to return. His whole family had thought he was dead,” says Erin. “When he came back, everybody was crying. Cousins, second cousins – he met family he didn’t even remember.”

Getting to know her relatives, Erin has even deeper respect and admiration for her grandfather now. “It’s clear they’re very traditional. Once we’re married, we join our husband’s family. But my grandpa was very different. He took a huge interest in me, and I’m his daughter’s daughter.”

Like her grandfather before her, Erin is eager to visit her newfound family in person as soon as international travel reopens. Until then, she’s embracing their digital homecoming, actively using WeChat to stay present in each other’s lives. “With zero contact, it’s so difficult to find your identity,” she reflects. “Connecting with your roots… it helps you know who you are in the world.”

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!