When Chinese genealogists talk about zupus (族谱), we often refer to them as the “holy grail”, the ultimate prize in family history research.

In fact, at My China Roots we have collected no less than 15,000 of these records to date, of which 1,687 have been digitized and are searchable online.

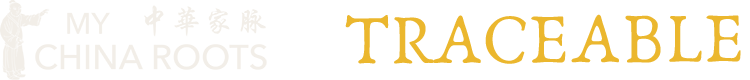

Why the fuss? These family history books are an invaluable record of family trees, clan traditions, migration stories and biographies, sometimes tracing back hundreds of generations.

Read on for 10 things you didn’t know about these records… and 10 reasons you should find yours!

*Note: Spellings of Chinese characters are based on the Mandarin pronunciation.

1. Chinese genealogies have been recorded for over 2000 years.

Genealogical records were kept as far back as 221 BCE (or pre-Qin Dynasty), alongside a strong oral tradition of passing family histories down from generation to generation. Initially a practice reserved to royal and aristocratic families, local Chinese clans1Clans are Chinese kinship groups based on a shared family lineage, surname, and/or locality. Many clan associations are still active in China and the diaspora, despite their functions and membership requirements changing significantly. For example, Havana’s Lung Gong Society was founded in 1900 for Chinese immigrants with the surname Lao 刘, Cuan 关, Chiong 张 or Chiu 赵. have kept what we now know as zupu since the late Ming/early Qing dynasty (the mid-1600s).

Zupus are also referred to as family, genealogy or clan books. In Southern Hakka, they’re called Chukpoo. In Chinese, they can be called 家谱 (jiāpǔ), 宗谱 (zōngpǔ), 房譜 (fángpǔ) 譜錄 (pǔlù) 家記 (jiājī) 世譜 (shìpǔ) 統譜 (tǒngpǔ) 家志 (jiāzhi) 支譜 (zhīpǔ) 通譜 (tōngpǔ) 會譜 (hùipǔ) 分譜 (fènpǔ) 譜牒 (pǔdíe) 牒誌 (díezhì) 譜系 (pǔxì) 玉牒 (yudíe) 譜誌 (pǔzhì) 譜傳 (pǔzhuàn) 家乘 (jiāshèng) or 族誌 (zúzhì)!

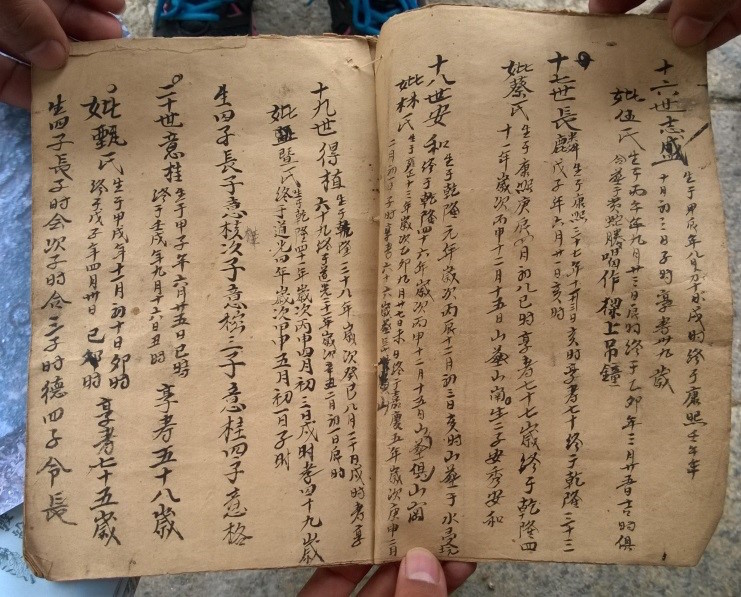

2. They have had a tumultuous history, but many survived against the odds.

Many zupus were destroyed or lost during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when campaigns against the ‘Four Olds’ rallied the masses to attack and denounce ancient habits, customs, ideas and culture. This included zupus, ancestral halls, and even tombstones.

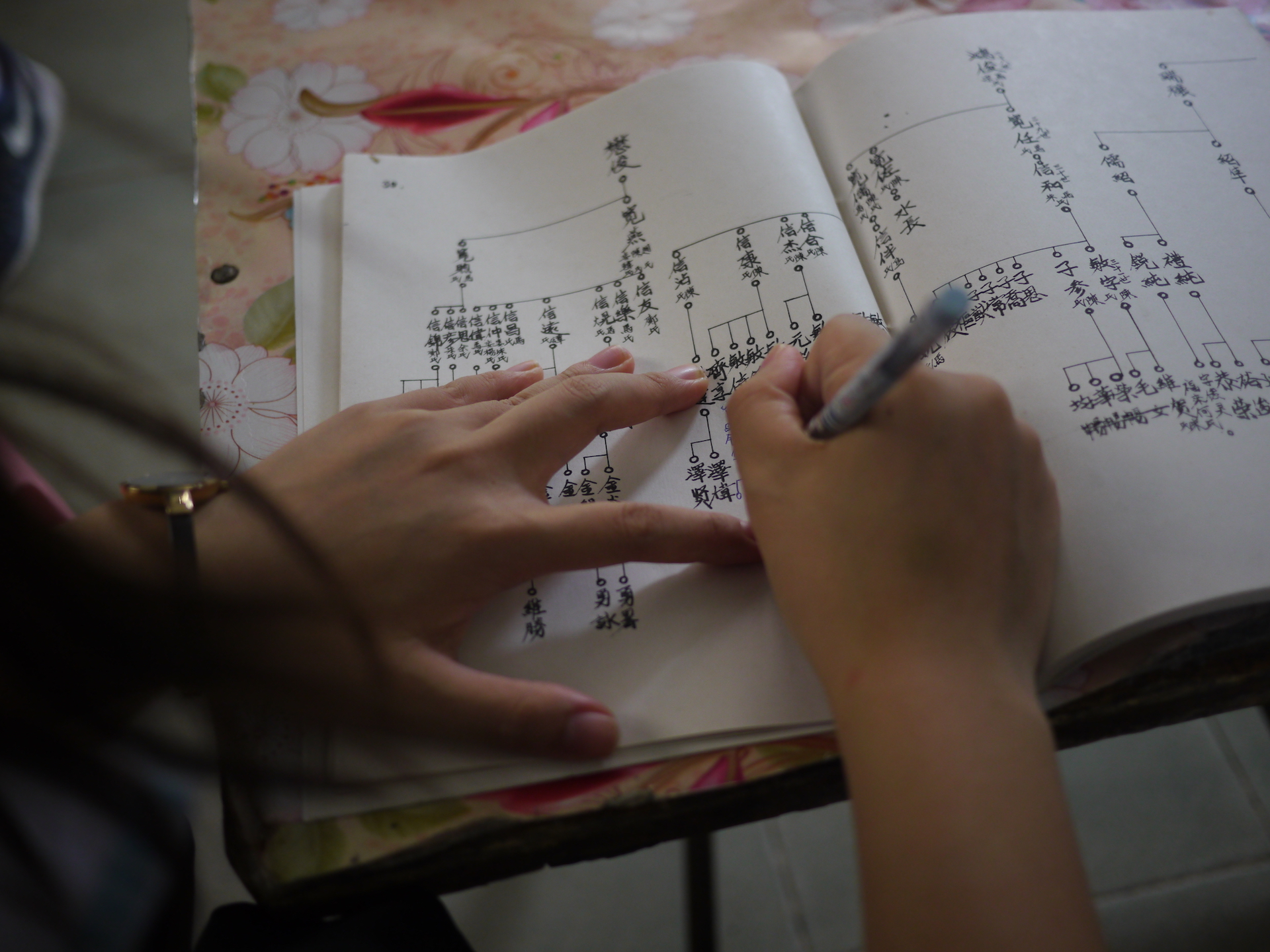

Thankfully, all was not lost. Many books were hidden away or shipped off to safety with relatives abroad. The 1980s saw a revival of genealogy and clan associations, with elders all over China putting their heads together to recreate and compile entire zupus from memory and scrawled notes on scraps of paper!

In one of researcher Waikwan’s favorite zupu success stories, one clan went to extreme measures to keep their zupu safe during the cultural revolution. They didn’t dare to bury it in their own village for fear of being found, so clan members took it to a neighbouring village, buried it in the earth for over a decade, and dug it up again in 1979!

3. Zupus can be pretty hard to decipher.

Zupus are written in traditional and formal Chinese, often using symbolisms, idioms and repetitive, embellished, “flowery language”. Even native Chinese speakers with a college degree have trouble understanding the content of a zupu and its writing style, vocabulary, and specific cultural and historical references.

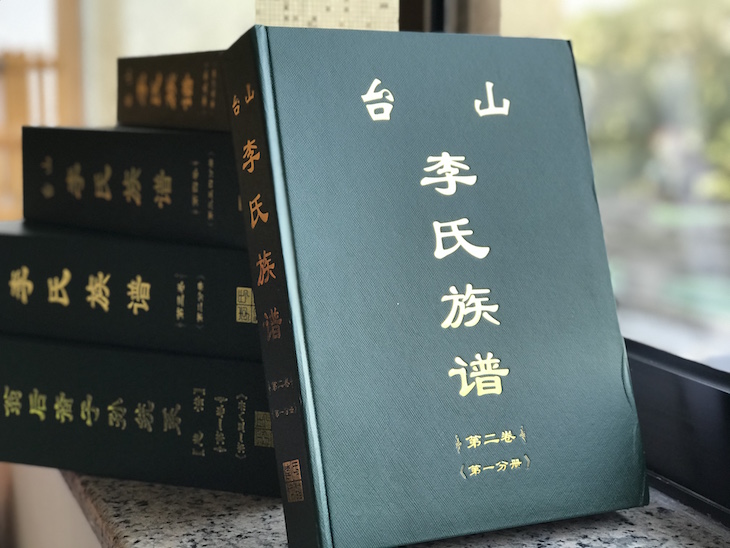

4. Some of them are thousands of pages long.

The Taishan Li Zupu, for example, is seven volumes and 8000 pages long! In an editor’s note in the Lanfang Zhou Zupu from 1616, Zhou Mengri laments the challenge of compilation:

“Having finished reading several jiapus from each individual branch, I closed them and sighed. Alas, the difficulty of zupu compilation, lies not the records, but in the combination of those records […] No matter how widely people have spread, how long time has passed, how many surnames people have been awarded; they all originated from one man. One multiplied to ten. Ten multiplied to one hundred. One hundred multiplied to one thousand. One thousand multiplied to 10 thousands. It is impossible to obtain all of this information only from books. If I am able to learn it from elsewhere, I will brandish my pen to write it to the zupu. If not, then there is nothing else I can do. Alas, how difficult it is to compile a zupu!“

5. Sometimes zupus contain rules for its clan members.

Typically, a zupu includes not only family trees and biographies, but also articles written for its clan members. These might include duties, behaviors or rituals. For example, a clan might prohibit its members from engaging in theft or from misrepresenting the clan; in the past, some even punished the violation of rules with expulsion from the lineage! Different clans also have their own systems and customs for ancestral worship. In the Xiecang Cai Zupu, for example, readers find the following instructions:

First, clan descendants take position. Raise the incense sticks, whilst kneeling and bowing three times. Present the silk and the tea, then invoke the gods to appear. Pour the wine and present the food and soup. Say the prayer aloud, then bow your head once, and rise. Perform the salute, kneeling and bowing three times. […]

6. And some will tell you how to name your children.

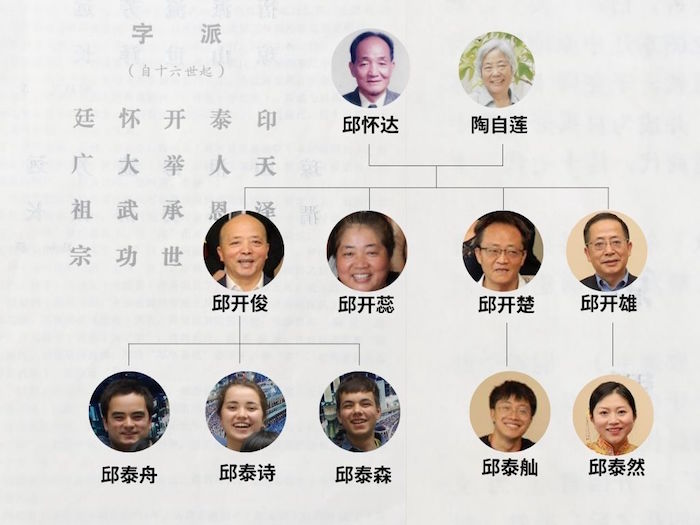

Most Chinese names are three characters long, with the clan name / surname first. Some families also follow generational naming traditions, which traditionally served to classify hierarchies between generations. Generation poems (bāncì lián 班次聯 or pàizì gē 派字歌) tell families which characters to use for either the middle or end character of a name: the generation name (zìbèi 字辈). In my family zupu, our generation poem (written here as zìpài 字派) has been followed since the 16th generation of the Qiu clan.

7. A zupu might tell you where your ancestors came from… and where they went.

Zupus can include fascinating epics on how your ancestors throughout history migrated within China, and also how they ended up abroad. For example, in the Xiān Yóu Xiàn Lín Clan Dà Zú Pǔ 仙游县林氏大族谱, we see that several clan members migrated to the port city of Surabaya in Indonesia:

Revered Jin Biaogong, the fourth generation of Guoling, left his hometown in 1928 with his eldest son Qing Qi. He and his son travelled across oceans to Surabaya, Indonesia, where he worked hard to make a living. He showed deep respect for his ancestors, strictly obeyed clan rules, and worked strenuously, showing no fear of hardships. Luckily, the heavens rewarded him for this, and his life abroad was successful. He left this legacy to five generations of descendants, of which there are 79 including 14 university students, and 9 who studied abroad.

8. The contents of a zupu must be taken with a pinch of salt.

Like any historical document, the contents of a zupu shouldn’t be taken entirely at face value. Part of a strictly patrilineal clan system, and compiled by the family to boast achievements and inspire pride, zupus generally excluded women, and ancestors who brought shame or dishonor to the clan. As wealthy families had more resources to compile and print zupus, peasant lineages are rare, and of course many individuals will never have been recorded because of migration, estrangement or premature death.

Until recently, women’s full names were almost never recorded in zupu, with wives’ surnames only appearing in their husband’s zupu (and often only if she gave birth to a male heir)! Thankfully, much of that changed with the 1980s revival of zupu compilation, and daughters, wives, sisters are included alongside their male relatives.

9. Tracking down your zupu is no easy feat.

If you want to find your zupu, a good place to start would be:

- My China Roots’ Zupu Database: our collection counts 15,000 zupus, including 1,600+ Guangdong and Fujian records searchable online!

- Family Search’s database of Chinese genealogies

- If you read Chinese, databases of China’s provincial libraries, in the province your ancestors came from.

If your zupu isn’t online, then your second port of call will be your ancestral village. Zupus might be kept in ancestral halls and temples, or by individual clan members. It’s also possible that your zupu was taken abroad by migrating ancestors, and could be held by a clan association in Malaysia or Singapore, like My China Roots client Nio:

“I was skeptical. My ancestors left Fujian seven generations ago, and our clan book was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. However, My China Roots found it 4000 km away… in Singapore!”

10. But it is well worth the journey!

While your zupu might be a challenge to track down and decipher, it is an invaluable piece of family history. After many stumbling blocks, My China Roots client Dennis Yeung describes the moment he finally found his ancestors’ names in the pages of a zupu tracing back 21 generations:

“When I saw their names right there on the page… it was, simply put, truly magical […] The link to our family heritage was restored. That single breathtaking moment made everything — all the work, all the anxiety, all the energy — completely worthwhile. The only experiences I can compare it to are my wedding and the birth of my children!”

In the words of Huang Chang, a civil official of the 6th rank in the Ministry of Rites and editor of the Lanfang zupu, writing on an auspicious Spring morning in 1404:

“As time goes by, a clan ultimately spreads and grows more branches, fathering more generations, and embarking on more migration waves. But by having a zupu, their ancestry can always be traced back, and there is no need to worry about descendants forgetting where they came from. If the readers of this zupu hold the knowledge of their origins in their hearts, then [our] efforts will not have been in vain, and the ancestors listed in the zupu will live forever.”

Find your zupu to unlock your family’s history.

If you have any questions about your family zupu, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese lineage and zupus. Simply click ahead to get in touch!